TAKSIM SQUARE

Taksim Square has become a space of visibility, rupture and conflict for the three prevailing climates of thought in existence in Turkey for the past 200 years. Professor Mete Tunçay classifies these strands as Islamism, Positivist-Westernism, and Socialism. If we are to define Taksim Square as an arena of contest between the different political currents leaving their mark on Turkey’s history, we must include within this framework one of the main actors of Turkish politics – namely, the “deep state”. After all, the incidents ranging from the Atatürk Cultural Center fire to the massacre of 1st of May 1977, taking place in Taksim Square, in which the deep state played the main protagonist are not at all few in number.

The Square may be considered a symbol, among others, of attempts by these currents to determine the center and push out all others. As this book is being written, it is clear that the remodeling of Taksim Square undertaken in the wake of the Gezi events is not about a mere change of scenery. While on the one side of the square we see the Atatürk Cultural Center, built as of the 29th of October 1946, being toppled down day by day, rising in parallel right across it is the Taksim Mosque, still under construction but coming to dominate the entire space. The mosque also overshadows the Taksim Monument – which is the Republic’s very first. It must, furthermore, not be forgotten that the Gezi events began with a decision to reconstruct the Artillery Barracks – part of which was destroyed by cannon fire when insurgents took refuge here during what is considered the “first reactionary uprising” in these lands, i.e. the 31 March Incident – upon the lands of Gezi Park, the Republic’s first park and a “protected cultural asset” – as well as that, of course, both the Artillery Barracks and later Gezi Park themselves were built on top of an Armenian Cemetery that used to be located here…

On the 13th of April 1909 (or 31st of March 1325 according to the Rumi calendar), an uprising by the name of the 31 March Incident (31 Mart Vakası) was sparked by the declaration of the 2nd Constitutional Era, as the very first revolt against “Westernization”. This lasted 13 days and was put down by means of the Hareket Ordusu (“Army of Action”) brought from Salonica by the Committee of Union and Progress. Insurgents taking refuge in the Artillery Barracks during the rebellion were captured after the barracks were bombed. These are the very same Artillery Barracks that were then completely demolished in 1940 and now wish to be rebuilt. The plan to open it as a shopping mall in fitting with the zeitgeist of the time is, of course, a whole other story!

This cycle is perhaps rooted in the fact that the accounts between Islamist and Westernist currents are simply never fully settled; and Taksim Square thus continues witnessing the history of the Republic of Turkey on the one hand, and that of coups, clashes and reconciliations between the three afore-mentioned political movements on the other.

TAKSİM MONUMENT

One of the first and most important symbols in Istanbul of the new Republic founded in Ankara, is the Taksim Monument. Erected in Taksim on the 9th of August 1928, thus transforming the space around it into a veritable square, the monument was commissioned to Italian sculptor Pietro Canonica by the Municipality of Istanbul. The model prepared by Canonica was approved by the Ministry of National Education, and donations were collected from the public as well for its construction, which cost 16,500 English pounds. It took 2.5 years for it to be completed. Once finished, its weight reached 184 tons. It was cast in Italy and shipped from Rome to Istanbul.

The 2-meter tall bronze sculpture was installed within an 11-meter pedestal made of pink Turin and green Susa marble. Its one side represents the Turkish War of Independence, while the other, the modern Republic of Turkey. The northern face depicting the victory of August 30th, 1922, was sculpted based on a photograph taken by Milliyet newspaper photographer Ethem Hamdi Bey at Kocatepe during Atatürk’s Great Offensive of August 26, whereas on the other face, enacting the founding of the Republic of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk is porgayritrayed in civilian attire along with İsmet İnönü, Fevzi Çakmak, soldiers and commoners.

The figure situated behind İsmet İnönü is Frunze, known as the founder of the Red Army and famous for his contributions to the October Revolution with his limited number of soldiers, while behind Marshall Fevzi Çakmak is Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Armies Voroshilov. It is claimed that the statues of these two Soviet generals had placed in Taksim so as to express gratitude to the Bolsheviks for their moral and material support during both the War of Independence and the founding of the Republic.

The soldiers on the remaining two sides of the monument are bearing flags – one of peace, the other of war. Above them are medallions depicting two women’s faces on separate sides; one is veiled, the other isn’t. While the Taksim Monument was being sculpted in Rome, the Academy of Fine Arts in Turkey held a competition, the winner of which was to be sent to work with Canonica as his apprentice. However, the fact that a young woman 22 years of age came in first place in the contest created problems. When certain hesitations arose over 22-year-old and single Sabiha Hanım’s trip to Italy, a letter was sent to sculptor Canonica, who responded saying that it would be more appropriate for a male sculptor to come on this internship. Sabiha Hanım’s journey to Italy and perhaps her becoming a sculptor were thus enabled by a directive Minister of Education Mustafa Necati sent to the Municipality. This was not the only conflict of opinion with Canonica: due to certain cracks found in the monument, he was not paid his final installment.

ATATÜRK CULTURAL CENTER

The Atatürk Cultural Center was taken down as this book was being written, as a result of long-winded legal and political struggles. The cultural importance of the demolition of this structure home to “Western-based” arts such as opera, ballet and theater in a time of the ascension of political Islam or by a nationalist-conservative government aside, its symbolic significance appears augmented by the fact that a heavily disputed mosque has been rising right across it as it falls. Looking at Taksim Square today, it is possible to say that pro-Westernists have been utterly vanquished. Making sense of the demolition of this cultural center in the hands of a regime that has brought up the reconstruction in Taksim of Artillery Barracks torn down many years ago to serve as a shopping mall is, however, a multi-layered task. Let us emphasize that this indexes a complex process demonstrating the hold of neoliberalism, and move on to focusing on the Cultural Center itself.

Its first sketches drawn by Architect Mimar Feridun Kip and Rükneddin Güney, the building was initially conceptualized as a grand opera house and its foundations were laid on the 29th of May 1946, marking the 494th anniversary of Istanbul’s conquest. However, things did not go quite as planned in the construction of this opera house, planned to cost 10 million liras and be ready to be opened on the 500th anniversary of the conquest. Left unfinished due to lack of funds, the building was handed over to the Ministry of Public Works in 1953. Construction resumed in 1956 with the appointment of Architect Hayati Tabanlıoğlu to oversee the project. Yet progress was slow due to ongoing funding issues.

The opera house planned to be completed in 7 years and cost 10 million liras eventually took 23 years to finish and cost a total of 93 million instead. It was finally opened on the 12th of April 1969 as the Istanbul Cultural Palace rather than the Grand Opera House. It contained a great hall with a capacity of 1381 people, a 750-person concert hall, a 350-person children’s theater, 350-person chamber theater hall, and an exhibition space. Its grand stage composed of three sections was the size of three volleyball courts. When up to capacity the “Palace” could hold more than 20 thousand people. The ballet Çeşmebaşı, composed by Ferit Tüzün, and Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Aida were performed in its opening ceremony.

The Cultural Palace is burning

On the 27th of November 1970, exactly 585 days after it opened, the Istanbul Cultural Palace burned down. As this happened, Arthur Miller’s The Crucible was being staged. This inexplicable fire ravaging the palace immediately prior to the military coup of March 12th, 1971 – a process in which the regime came to hunt down intellectuals – would only take on meaning after the 12th of March.

A Beyoğlu Fire Department operator, Sabri Kodalak, would write down the following words in his logbook on the night of November 27, 1970: “The time: 22.58… Tel. 45 50 14… Department office, 23.00… The unnumbered masonry building belonging to the Ministry of National Education, serving as the Cultural Palace, with a panelled and upholstered interior, composed of three storeys from the front and seven from the rear, is on fire, which started in its left-hand and rear section, but has spread to the stage, hall and roof…” This was to be the first official record of the infamous “Cultural Palace Fire”, which would become a benchmark within the political developments taking place in Turkey post-March 12. The actors on stage at the time of the incident recounted the fire to Milliyet. Nihat Akcan: “I suddenly heard laughter from the audience. Set decorator Ahmet Aslan had rushed on stage and was saying something. I looked up for a prompt. The right corner of the stage was ablaze.” Kerim Afşar: “I had my back to the left wing. Suddenly, a strange man burst in from the right wing and came on stage trying to say something. Seeing him, the audience began giggling. I was deeply annoyed. Forgetting all else, I started walking up to him in anger. It was right then that I heard a terrible scream from the audience. A woman was yelling, ‘we’re on fire!’.”

No lives were lost in the fire, though Sultan Murad IV’s caftan, sword, robe, a firman (imperial edict) he had sent to Kösem Sultan, a portrait of his by a famous Italian painter, and a precious Holy Quran (“Kur’an-ı Kerim”) inscribed by one of his calligraphers Hafız Mehmed brought from Topkapı Palace and put on display in the Istanbul Cultural Palace for the gala of the play Murad IV were all reduced to ash.

Though an electrical fault and possible neglect were dwelled on as reasons for the fire, during which the building’s fire-extinguishing systems and telephones also did not function, a definite conclusion as to its cause could not be reached. The palace had been opened in disregard of architect Hayati Tabanlıoğlu’s warnings that it was not yet fully ready, that its technical infrastructure was still incomplete, and that there weren’t enough technicians for the management of the stage. It burned to the ground within 45 minutes.

According to a statement by representatives of the Artists’ Association of Turkey (Türkiye Sanatçılar Birliği), two days prior to the fire the National Student Federation of Turkey (Türkiye Milli Talebe Federasyonu – TMTF) had handed out flyers signed the “Theater Censorship Committee” (“Tiyatro Sansür Komitesi”), asking for “plays that were not nationalist and respectful of the sacred (“mukaddesatçı”) to be brought off stage”. The Artists’ Association issued a counter-statement, and applied to the Prosecutor’s Office for the “insurance of the safety of life and property of association members, all artists, and audiences”.

Various organizations and institutions asked for efforts to be made to uncover the true cause of the fire and condemned those responsible in statements they made. Yet, investigations – as expected – bore no fruit, and the search for the possible arsonist or arsonists was discontinued. That is, until the military coup of March 12, 1971. In a decree he issued towards the end of March, Istanbul Martial Law Commander Faik Türün stated the following after announcing that 27 people had been arrested for the “Marmara” ship incident: “The explosion of the ‘Ayşe’ blast furnace and the Cultural Palace fire taking place prior to the proclamation of martial law are also being thoroughly investigated by our Command. Saboteurs or those deemed negligent in these incidents shall suffer the blow of the damning fist of justice – even if belatedly.”

Leftists charged with acts such as setting the Istanbul Cultural Palace on fire, as well as sinking the Marmara passenger ship on the 5th of March and the Eminönü car ferry on the 28th of June were put on trial in 1972. As detailed in the prosecutor’s “indictment”, 24 people including those kept under custody for over a month and those subjected to torture in the “counter-guerrilla” torture center (Ziverbey) so as to admit to charges interrogators wished to pin on them were brought before court on grounds of being responsible for “the Cultural Palace Fire, Kastamonu cargo ship sabotage, Marmara ship sabotage and Eminönü car ferry sabotage, as well as committing the crime of establishing a Workers’ Union.” The prosecutor then asked for a death penalty for 17 of these defendants.

The post-March 12 military junta declared that the Cultural Palace fire taking place almost two years ago, as well as a series of bombings and acts of sabotage occurring around the same time, were all part of preparations for a coup within the army. In another court case opened in May 1972, 84 people – mostly military officers, including full generals – were accused of ordering the arson of the Cultural Palace and the sabotage of various ships. According to one of the prosecution’s claims in this trial that came to be known as ‘the bomb case’, defendant Orhan Kabibay, one of the May 27th putschists, had received 4500 TL from Bülent Ecevit to sabotage a ship. It should be remembered that this claim was featured in newspapers as if a verified fact.

In 1975 all defendants, including those standing trial facing death penalty, were released and then acquitted. They even later won suits for damages. While those accused with sabotage were absolved, defendants in the Revolutionary Workers’ Union case (Devrimci İşçi Birliği) included here were convicted.

Yet this did not prevent Atilla Koç, who served as Minister of Culture in the 59th AKP government from 2005 to 2007, from referencing the fire suffered by this building in 1970 in criticizing those objecting to the present-day demolition of the Atatürk Cultural Center saying, “Unfortunately the anarchist communists of the day (and I say this for it to be known who is a friend of art, who spits in its face, who burns it down, who puts its back up) sabotaged this site for being ‘a place of entertainment for the bourgeoisie’ and burned it to the ground.”

Becoming the “Atatürk Cultural Center”

The new obstacle to the renovation of the Atatürk Cultural Center (AKM) came in the form of certain intellectuals and artists. They put out a declaration opposing the building’s restoration with public money while the people went hungry, and called for a campaign to be started. Nobody took them seriously.

The edifice that had become largely unusable after the fire with its caved-in roof was once again entrusted in the hands of architect Hayati Tabanlıoğlu. On the 7th of November 1971, the then Minister of Culture Talât Sait Halman inspected the building under restoration and gave the good news that it would reopen on Republic Day in 1973, making the following announcement: “The Republican era is not for building palaces; they are a thing of the past, left back in the days of empire. It is for this reason that this place is from now on to be called the ‘Atatürk Cultural Center’.”

It was the 6th of October 1978 by the time the center was opened. The opening festivities lasting from the 6th to 18th of October included: the Yunus Emre Oratorio performed by an orchestra conducted by Hikmet Şimşek, a performance of Othello, a screening of Al Yazmalım (The Girl with the Red Scarf), a recital by İdil Biret, a Ruhi Su concert, and various exhibits from sculpture to caricature.

The AKM’s journey over the course of time and its demolition

The Atatürk Cultural Center hosted a wide array of cultural and artistic events ranging from festivals to concerts, theater to cinema, and ballet to opera over many long years. On the 1st of November 1999 the Istanbul No.2 Regional Board for the Protection of Cultural and Natural Assets declared the Cultural Center a “Grade I Registered Cultural Asset” within the zone of the First Degree Urban Heritage Site. The edifice was thus brought under protection. Yet the Minister of Culture and Tourism at the time, Atilla Koç, said that the building had reached the end of its lifetime by 2005 and proposed that it be taken down. This suggestion was met with great opposition since nobody believed that the Cultural Palace would be reconstructed once demolished. On the 31st of May 2008, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism brought events at the AKM to an end. The building began awaiting restoration. Yet the project in this regard was annulled in court as a result of a case filed by the Union of Culture, Art and Tourism Workers. In 2009, a protocol was signed between all interested parties for the building to be restored and reinforced in a manner preserving it as is. Murat Tabanlıoğlu, son of its original architect Hayati Tabanlıoğlu, was charged with this restoration. In February 2012 the Sabancı Foundation pledged to contribute 30 million liras to this project. Restoration efforts hence began. The opening was planned for Republic Day, the 29th of October 2013. Yet in 2013 work on the building was halted upon orders by the Ministry of Culture. What happened to the donation made by the Sabancı Foundation, on the other hand, remained a mystery.

As the month of May came to a close, the Gezi Resistance began. The Atatürk Cultural Center itself became one of the symbols of this resistance due to banners strung up on its front façade during the uprising. Making statement after public statement about these protests at the time, then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan uttered his well-known outburst, ‘God willing, the AK M will be torn down’ on the 6th of June 2013… To bracket: one of the banners hung up on the Atatürk Cultural Center during the uprising read ‘Shut up Tayyip!’. In an exhibit titled ‘Memory Spaces’ curated by architect Murat Tabanlıoğlu in the 14th International Venice Biennale in June 2014, a photograph of the center covered in banners was also featured. The one that said ‘Shut up Tayyip!’, however, had been censored, blocked out by extending a tree in the image using photoshop. This ‘memory’ remains a black stain in the past of the building that has become synonymous with the name Tabanlıoğlu.” Quoted from the news article prepared by Aslı Uluşahin for Bianet on the course of the building’s journey through time.

Its entrance closed off with wooden panels after the Gezi protests, the edifice started being used as a police station. The Chamber of Architects filed a complaint regarding this in April 2014. In October 2014 it was decided that there were no grounds for prosecution. At this time the building’s façade was being used as advertisement space.

President Erdoğan made a detailed statement regarding the fate of the AKM in 2017. “Atatürk” had unsurprisingly been eliminated from its name, as it was now to be called the ‘Istanbul Cultural Center’. Aimed to be the largest opera building with the best ever acoustics, specifics on the new AKM that was to serve “the entire populace and not a portion of elites” were as follows:

- The AKM shall be an entire complex, rather than a single building. Its total surface area shall cover 100,000 square meters.

- The grand salon shall have a capacity of 2500 people, designed as a great red dome.

- Annex structures shall have green roofs and be environment-friendly. These will house theater, conference and cinema halls, along with an 885-capacity car park.

- The theater shall hold 800 people, the conference hall 1000 people, the cinema hall 285 people, and the chamber theater 250 people.

- The programs and performances shall be projected on a giant screen outside.

- A Bosphorus-view restaurant shall be opened on the topmost floor.

Taksim Square shall remain closed to vehicular traffic. The aim was for the new structure designed by the former architect’s son Murat Tabanlıoğlu to be completed in the first quarter of 2019. The AKM has, in the end, been demolished as this book was being written (2018). The rest we shall witness all together.

BLOODY SUNDAY

The incident in which 2 people lost their lives and 200 were injured as a result of an attack in Taksim Square by right-wing groups on a march by university students on the 16th of February 1969, protesting the arrival of the Sixth Fleet – established in 1950 for U.S. control in the Mediterranean – in Istanbul, took its place in the pages of history as the “Bloody Sunday”. As influential as the anti-imperialist spirit of Turkey’s rising socialist movement in these developments was the impact of U.S. President Johnson’s letter to Prime Minister İsmet İnönü during the 1963-65 Cyprus crisis. His letter dated 1964 that more or less went, “You cannot intervene in Cyprus and you cannot use the arms we have given you, if you choose to do so then we shall intervene in your soil instead,” as well as İnönü’s response saying “a new world order will be established, and we shall take our place within it” were shared with the public only by 1966, and this became an instigator of further anti-American sentiment. This was not, however, the case for right-wing factions in Turkey. The belief that the Americans were “our guests, as well as friendly forces helping with our defence against Russia” widely prevailed in the political right. The U.S. stood by Turkey’s side in its combat against communism, and as such had to be supported. American fleets coming to Turkey in this political setting, however, were being protested, with their soldiers roughed up, chucked paint at, and “driven” into the sea. During protests against the arrival of the Sixth Fleet in 1968, the police – though legally forbidden from entering university campuses – raided student dormitories. Vedat Demircioğlu lost his life in this raid. The official explanation given was that he had fallen from a window, while his friends said it was murder. This was the political climate in which the Sixth Fleet was coming to Turkey in February 1969. Following small-scale demonstrations in Ankara, İzmir, Trabzon and Istanbul against the fleet’s arrival in Istanbul, student and worker organizations decided to hold a mass march and rally in Istanbul on the 16th of February against imperialism and the system of exploitation. The necessary permission was obtained from the Governor’s Office for this demonstration, in which 76 youth organizations were to participate.

Yet after this protest program was announced, the Association to Combat Communism (Komünizmle Mücadele Derneği) and the right-wingled National Turkish Student Union (Milli Türk Talebe Birliği) held a “Respect the Flag” (“Bayrağa Saygı”) rally on the 14th of February. What instigated this rally was the hoisting of a flag bearing a photograph of Demircioğlu, who had lost his life a year ago, on Beyazıt Tower on the 11th of February 1969. The next day this was featured in the press as “a red flag flown on Beyazıt Tower”. Addressing the crowd in their rally a couple of days later, President of the Associations to Combat Communism İlhan Darendelioğlu was calling on them in the following words: “It is time to bury deep down underground these traitors betraying our country… On Sunday, communists will hold a rally. There, we shall fight them. Whoever has a gun, come with your gun; if you don’t, then bring an axe …”

On the 16th of February, while anti-imperialist protestors were gathering in Beyazıt in order to march towards Taksim, rightists heeding the call to “teach communists a lesson” came to Taksim Square. After a mass prayer here, their stone-and-club-armed wait began. Youth organizations meeting in Beyazıt Square started marching, passing Sultanahmet, Sirkeci, Eminönü, Karaköy and Dolmabahçe to finally reach Taksim Square, where the police cut them off and made them enter the square in small groups. Right-wingers overcame the police barricade and attacked the arriving anti-imperialist demonstrators with stones, clubs and knives. Accompanied by chants of “Allahu akbar”, the attackers stabbed protestors Ali Turgut Aytaç and Duran Erdoğan to death, wounding approximately 200 more. The police did not do much to intervene.

Here is how Istanbul Technical University Student Association President Harun Karadeniz would later describe that morning in his book Olaylı Yıllar ve Gençlik (Eventful Years and Youth):

“The first bit of news came from the Dolmabahçe Mosque. Apparently, a crowded group had gathered around it and was praying. Towards 10.00 am I went over to see what was going on first-hand. A majority of the crowd were bearded and skull-capped. These were the ones that would attack us. They were foreign to the city, eyeing their surroundings in awkward yet curious silence… I thought: they are sincere, they have faith, they have come here to go all the way, do whatever necessary, risk death if need be. They will save their religion and their country, even if this costs them their lives…”

It was as clear as daylight that there would be an attack, yet still… Harun Karadeniz explains as follows: “No matter how inadvisable the conditions, we were going to walk unarmed and unprepared for a fight. Yes, that was our mindset then, and that was what we did. Later on, there were those who found us at fault and criticized us.”

All political parties, other than the Justice Party (Adalet Partisi) that was in power, called for the resignation of the then Minister of the Interior Faruk Sükan. Sükan, on the other hand, put the blame on leftist students and remained deaf to reactions, saying the police had done whatever their duty required. Certain members of parliament from the Justice Party jumped on this bandwagon of blame. Not one soul was penalized for this attack that took the lives of two people and injured hundreds. The person holding the knife and the police officer standing by simply watching, caught in a photograph showing the exact moment Ali Turgut Aytaç was stabbed to death, were questioned. The suspect Seyit Atmaca said, “I found the knife on the ground” and was immediately set free, while the police officer Haşim Bozkurt was first arrested, then found not guilty in court and released.

18 years after this incident, Nokta magazine revisited the Bloody Sunday case in its issue dated February 1st, 1987, and asked the period’s Istanbul Governor Vefa Poyraz and Minister of the Interior Faruk Sükan for their comments. According to Poyraz, there was no “reactionary movement” at the time, in his words: “As you know, there is a political party that has since been shut down (the Workers Party of Turkey). On the one hand is a march involving members of that party, on the other is the right reacting against this. Leftists set out to march on grounds provided by Law no. 171; there were those who wished to obstruct this march, the administration sought to prevent them. But then in Taksim, a popular upsurge took place all of a sudden, and an unexpected confrontation occurred, which unfortunately cost the lives of two individuals.” Faruk Sükan, on the other hand, provided the following explanation: “You’re asking about the communist incidents you call ‘Bloody Sunday’… If we hadn’t taken precautionary measures, they would have wrought much greater havoc. Leftists, that is. It’s crystal clear. It was all about a communist manifesto deal in Turkey.” The long-standing state and conservative government tradition of blaming the victim in all such incidents was thus continued.

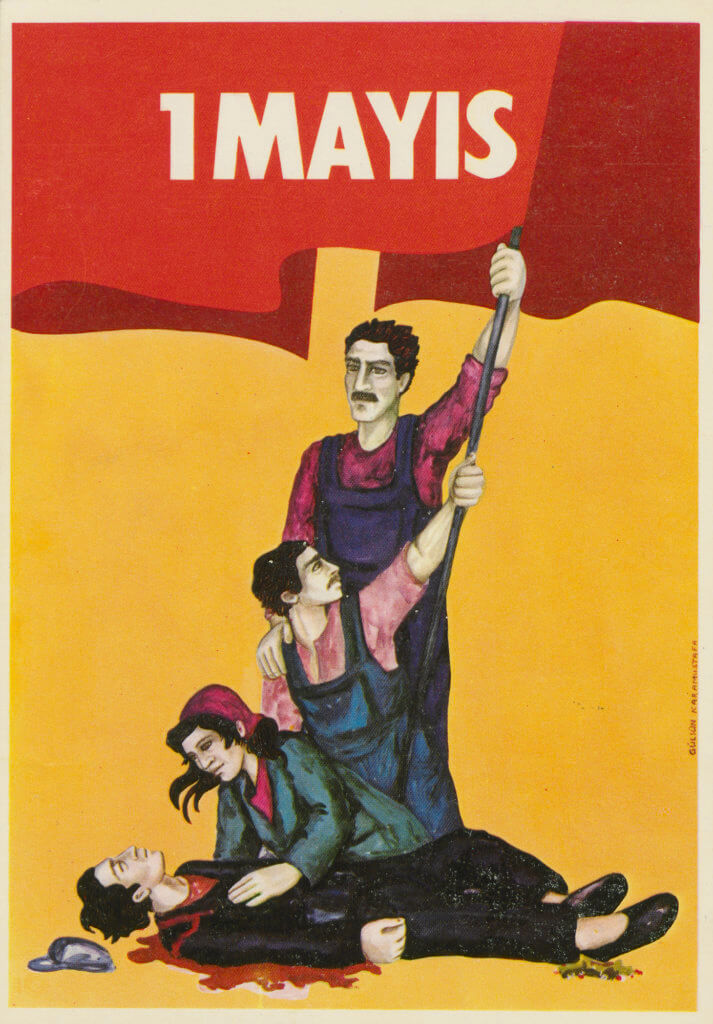

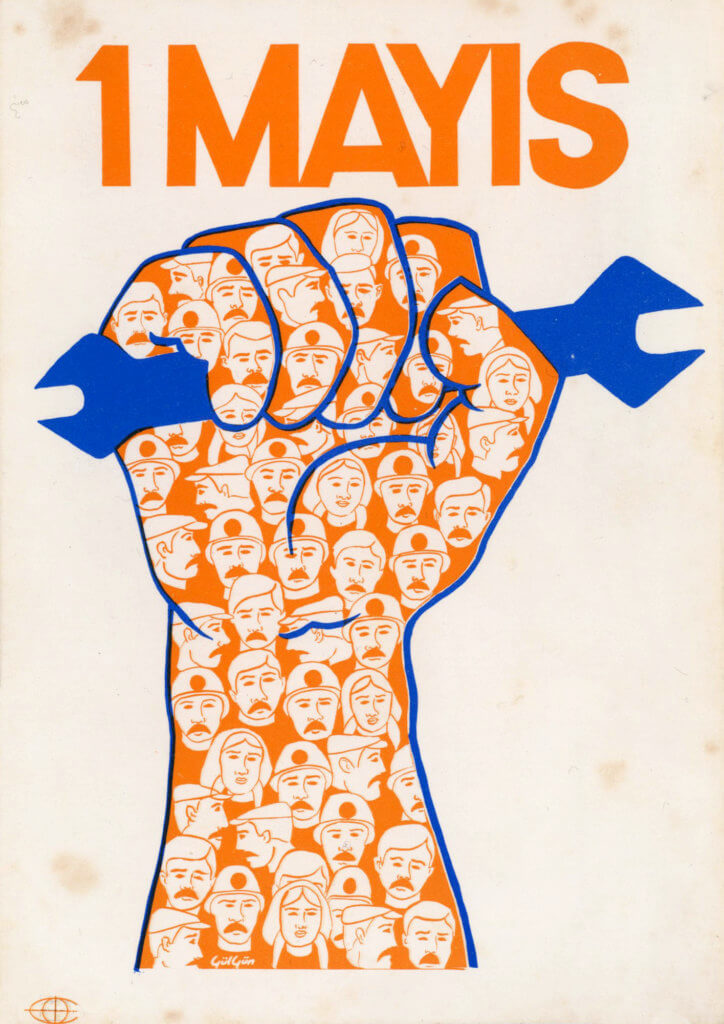

1ST OF MAY 1977

1st of May celebrations highlighting the struggle and unity of the working class have been a constant matter of conflict and contestation between the state, workers’ organizations and revolutionary organizations. Officially declared “Labour Day” in 1923, it took almost 50 more years before May 1st could be celebrated publicly and collectively.

The first mass celebration of May 1st took place in 1976 in Taksim Square. This coincided with a time in which the Confederation of Progressive Trade Unions of Turkey (DİSK) had grown stronger in terms of rights struggles and organizing. Industrialization also played a part here – for instance, development in the automotive sector led to an increase in the number of workers, and this in turn to their organizing for the purpose of revolutionary struggle. When revolutionary cadres imprisoned after the coup of March 12th were released with the amnesty of 1974, they came out to meet a dynamic youth and workers’ movement. Though mainstream ones remained steady, the discussion and debate taking place within and outside prisons post-March 12 also brought about the establishment of brand new organizations in the left. It is, therefore, possible to speak of a multitude of leftist organizations from the mid-1970s onwards, with strained relations at times breaking out into internal conflict, lacking an umbrella under which to be gathered. It is, however, also possible to mention the existence of a strong popular movement involving millions despite all of these splits and divisions…

DİSK had held a crowded rally with the participation of 150 thousand people on the 1st of May 1976 in Taksim Square. The rally attended by workers and revolutionary youth alike had ended without incident. Emboldened by this success, DİSK hence decided to organize an even more spectacular event to celebrate May 1st the following year, in 1977, with Taksim as the venue once again. The May 1st of 1977 was out to be a mighty tour de force of Turkey’s left, and almost all leftist organizations were, therefore, preparing to join the celebrations in Taksim en masse.

Yet there were also those who were less than comfortable with such massive 1st of May celebrations in Turkey. Writers on the right explicitly voiced this in their columns in the days leading up to May 1st, 1977: “Cars will be vandalized, glass windows were broken; we hope to God we are mistaken but there will be blood.” There was also tension within the left. The permission to celebrate May 1st in Taksim square had been given to DİSK. As the organizer, DİSK wished to keep the rally limited to its own rules. It, therefore, did not want groups it was not on quite good terms with such as Halkın Kurtuluşu (People’s Liberation), Halkın Yolu (People’s Way), Halkın Birliği (People’s Unity) and Aydınlık (Enlightenment) participating in the celebration. The groups Devrimci Gençlik (Revolutionary Youth) and Kurtuluş (Liberation), on the other hand, were only to be allowed into the square with certain slogan restrictions.

Aydınlık announced prior to the rally that it would not participate in order to prevent possible provocations. DİSK had informed the police and security forces as to where each group would be positioned in the square and charged 20 thousand of its members dressed in special attire with maintaining this order. 15 police chiefs, 315 captains, 3094 officers, 207 guards, 81 motorized squads, 9 panzers and a gendarmerie regiment were to secure the May 1st route. Around 500 thousand people coming to Istanbul from various provinces in order to celebrate Labour Day on May 1st, 1977, filled Taksim Square in the organization led by DİSK. Even the tension with the three groups had been settled somewhat amicably, as they had been allowed to march in the very back of the procession on condition that they left some space in between.

It took longer than expected for the groups to enter the square due to the high turn-out, and the rally was prolonged. Around 19.00, as the then DİSK President Kemal Türkler reached the end of his speech, gunshots – initially claimed to be one, later two – were heard from Abdülhak Hamit Avenue leading up to Taksim from Tarlabaşı. Hundreds of thousands of people began stampeding out, trampling on each other. As chaos and panic reigned, the crowd was fired at with long-range rifles from the Water Administration building and the Intercontinental Hotel (the Marmara). Right at this moment, a panzer rolled into the square out of the blue and began shooting pressurized water and running over people.

Two panzers sped into the area from the Taşkışla way. They began moving towards the Atatürk monument passing by the hotel and raking the already bottlenecked crowd from that side so as to force them to flee back towards the platform. I clearly saw a light-haired woman with colourful clothing being run over by a panzer. The panicked dispersal of the crowd became more frenzied after this. The panzers passed by a couple more times in the same manner.”

Quoted from the account of Şükran Ketenci, a writer for the Cumhuriyet, observing the incident from in front of the hotel.

Hundreds running for their lives made for the Kazancı Hill. A blue Fiat truck had parked right at the top of the hill just before everything went awry, and casually strewn wheelbarrows were preventing entrance to Kazancı. Just then, a white Renault dashing out of a garage below the hill hurtled up, firing repeated shots onto the crowd with a long-range rifle protruding from its front window. People scattered about in utter shock and ran over each other. The white Renault with the Thompson, on the other hand, curved towards Sıraselviler and disappeared from sight. In this scramble 28 people lost their lives due to being crushed or to suffocation, 5 more were killed by gunshot, and 1 run over by a panzer, while around 130 were injured. Many of those who died were trapped because of the truck parked at the entrance of Kazancı.

Statements made by Istanbul Governor Namık Kemal Şentürk and Chief of Istanbul Police Nihat Kaner following the incidents are of the sort that demonstrate how state officials and conservative politicians have not changed their approach despite the 50 years that have gone by: “…The rally organized by DİSK was being held in a regular fashion. However, just before the crowd was to disperse, certain groups slipped into the Taksim area. These have been identified as the main cause behind the clashes through various witness testimonies and documents. Police forces heroically risking their lives to fend them off prevented an even worse outcome. Even those looking to loot and plunder (“çapulculuk”) were stopped short with immediate precautions.”

Prime Minister Süleyman Demirel, for his own part, uttered the following words before entering an emergency Cabinet meeting on the very night of the incident: “Kemal Türkler would simply not end the rally. He kept dragging it out. The incidents caused by Kemal Türkler, that murderous villain, are a sequel of June 15th… They have been brought to pass by a Maoist group… Mayor Ahmet İsvan of the People’s Republican Party (CHP) was also there in the DİSK rally. There were members of TİP (the Workers Party of Turkey) present as well. See, this is what happens when you don’t consider communism a threat.”

On the 6th of May CHP Leader Bülent Ecevit met with President Fahri Korutürk. After this meeting he said that he had “certain suspicions”, and elaborated on these suspicions the next day in the CHP’s İzmir rally as follows: “I am of the impression that certain entities existing within the state or at least backed by state power, yet exempt from the due supervision of the democratic state of law, are the principal cause of these events, and that both wings of the government are bent on taking advantage of their deeds rather than taking the necessary measures to prevent them.” According to what Mehmet Ali Birand said in his book 12 Eylül Saat: 04.00 (September 12, 04.00 a.m.), Ecevit’s “suspicions” were related to the Special Warfare Unit (Özel Harp Dairesi) publicly known as the counter-guerrilla force.

470 people were arrested in the wake of the incident, and 98 of these were prosecuted. 6 public prosecutors were charged with the case, yet no investigation was carried out, and 6 deputy public prosecutors sent to court the suspects at hand with a 41-page indictment based on police investigation files comprising 17 folders. The defendants were none but protestors arrested in Tophane and Dolmabahçe right after the event, and the case was turned into an indictment in a record 27 days. For some reason, however, the prosecutor’s office did not feel the need to carry out an investigation itself.

The indictment in the 1st of May case stated that the first gunshot came from Abdülhak Hamit Avenue, that two more shots then followed, and that two gunshots were also heard from in front of the Intercontinental. Here is how other sites of shooting are specified: “These evidently non-coincidental shots were followed by serial gunshots fired simultaneously from various floors and sections of the Intercontinental, from within the adjacent construction site and florist’s, from above the PTT building, and from above or around Pamuk Pharmacy.” Bullet holes were observed in the hotel’s first-floor window panes facing Taksim square in sections 7, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 16 from left to right. The prosecution demanded in the very first hearing that the actual perpetrators be brought before the court. Many police officers on the witness stand were later seen to withdraw their testimonies, including one who had identified 49 defendants at once.

The mainstream media alleged in the immediate aftermath of May 1st that the incidents were the result of internecine strife within the left. The political right in Turkey has embraced this thesis to this day. The entire press establishment, save for newspapers Cumhuriyet, Politika and Vatan harped on this theme from May 2nd onwards, saying “Maoist traitors shed blood on Labour Day”.

In a dossier it prepared on the 4th of May 1986, Nokta magazine interviewed both those in the white Renault and the panzer drivers. The white Renault belonged to the First Division. The panzer drivers claimed to have entered the square to bring under control clashes that had broken out. The incident was never brought to light. The forces that lay behind the truck on Kazancı Hill, the white Renault or even the gunshots fired from the Intercontinental were never revealed. It was, however, claimed that CIA agents had checked into the hotel a day prior to the event, and that this had later been covered up with their records erased. In the same period, the National Intelligence Organization (MİT) warned Prime Minister Süleyman Demirel of a possible coup. The very day the 1st of May investigation produced an indictment, Bülent Ecevit survived an assassination attempt.

Neither Demirel who had forewarned Ecevit of an attempt on his life, nor Ecevit who suffered the assassination attempt did anything to shed light on the 1st of May massacre or the activities of the Special Warfare Unit. The only thing done was that the Land Forces Commander was retired on the 1st of June 1977, right after the incident.

A CHRONOLOGY OF MAY 1ST IN TAKSİM

In 1912, the first May 1st celebration took place in Istanbul, in the Belvü (Bellevue) garden in Pangaltı.

In 1923 the 1st of May was legally declared “Labour Day” (“Amele Bayramı”).

In 1924 the government banned mass public May 1st celebrations. The Law on the Maintenance of Order (“Takrir-i Sükun Yasası”) enacted in 1925 prohibited the celebration of Labour Day, and this ban remained in place for many long years.

In 1935, May 1st was called the “Spring and Flower Festival”, and it was declared an unpaid holiday.

In 1975, the 1st of May was celebrated in an indoor meeting held in the Tepebaşı Clubhouse.

In 1976, a publicly attended, crowded May 1st celebration took place for the first time after many years, with the Confederation of Progressive Trade Unions of Turkey as the organizer.

In 1977, the best-attended 1st of May gathering was held in Taksim with 500 thousand present. In the chaos ensuing in the wake of gunshots fired, 34 people were killed and hundreds injured.

In 1978, hundreds of thousands took part in the celebration in Taksim Square.

In 1979, the Martial Law Command did not allow a rally in Istanbul and declared a curfew. Regardless, 1st of May was celebrated in rogue fashion by hundreds of thousands on the streets of Istanbul. In 1981, the National Security Council revoked the status of May 1st as an official holiday.

In 1989, Mehmet Akif Dalcı, claimed to have been in the ranks of Cephe (the Front) trying to make its way towards Taksim from Tarlabaşı, was killed by a police bullet.

In 1996, around 150 thousand people participated in the 1st of May celebrations held in Kadıköy on grounds that Taksim Square was off limits. Kadıköy was also home to the most crowded demonstration in 2006. Various unions and groups marched towards Rıhtım (“Waterfront”) Avenue around 12.00. After a rally was held here, the crowd was completely dispersed by 16.00.

In 2007, the 30th anniversary of the events of 1977, DİSK President Süleyman Çelebi waged a campaign that carried the demand for Taksim beyond small leftist groups, making it the political claim of Turkey’s most important union. Throughout the day, the police kept trying to stop groups using firearms, pepper spray and tear gas. More than 100 were wounded. 580 were arrested according to the Governor’s Office, while other sources gave this number as near 700. After this hassle, however, a group of around 1000 were able to enter Taksim and make a statement to the press in front of The Marmara hotel.

In April 2008, May 1st was allowed to be celebrated as “Labour and Solidarity Day”, yet groups were unable to approach Taksim.

In April 2009, the 1st of May was once again recognized as an official holiday as per a motion made in the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. Unions were allowed to celebrate in Taksim on condition, as put forward by the Governor’s Office, that “an acceptable number” be admitted. More than 5000 were thus able to march into Taksim from Harbiye, as a result of which the 1st of May was de facto celebrated in Taksim after a long break.

In 2010, the 1st of May was celebrated in Taksim with the participation of around 140 thousand people

In 2011, songs were played and sung in Taksim Square in joyous celebrations. Group Yorum gave a mini concert.

In 2012, many intellectuals, artists and union representatives made speeches on the platform set up in Taksim Square. Songs were sung and folk dances (“halay”) were danced.

In 2013, Tayyip Erdoğan disallowed 1st of May celebrations in Taksim, saying “It’s my call whether to give permission or not; if I choose not to, I don’t,” in a meeting with confederation leaders. The reasoning given was technical issues, construction work, and preventing people from falling into pits that had been dug out here. Governor of Istanbul Hüseyin Avni Mutlu declared that the square would most definitely be closed off to 1st of May celebrations, citing the excuse that it was a construction site. The police intervened on many groups setting out to reach Taksim.

In 2014, celebrations in Taksim Square were banned by the Istanbul Governor’s Office. Ferries were cancelled. The Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality announced a blockage of all roads leading up to Taksim. The police attacked protestors wishing to reach Taksim in various neighbourhoods of Istanbul. Many were injured and taken under police custody.

In 2015, arrests and the police siege laid on Taksim left its mark on celebrations in Istanbul. Groups attempting to march towards Taksim from Beşiktaş to celebrate 1st of May there faced heavy police intervention. A young person was stabbed in the stomach in Beşiktaş. Istanbul Governor Vasip Şahin announced that 203 had been arrested in a statement he made. He also informed the public that 6 police officers and 18 protestors had been injured. The crisis desk manned by volunteer lawyers, on the other hand, stated that detainees numbered at least 356 by 20.30.

In 2016, unrest broke out between police officers and members of the HDP (People’s Democratic Party) at a checkpoint leading into the Bakırköy Public Bazaar area. When the tension escalated further at the second checkpoint, the police resorted to tear gas.

In 2017, the 1st of May Labour and Solidarity Day was celebrated in the Bakırköy Public Bazaar area with a call by DİSK, the Confederation of Public Workers’ Unions (KESK), the Union of Chambers of Turkish Engineers and Architects (TMMOB) and the Turkish Medical Association (TTB). 165 people were arrested in celebrations all over the city.

In 2018, May 1st was celebrated jubilantly across Turkey. Yet the organization in Istanbul took place in the Maltepe rally area upon decree by the governor’s office. At least 84 protestors were arrested in Istanbul, most of whom had been attempting to reach Taksim Square.