Among occupants of the building were Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu, writing his poems in one of the two-storey office spaces on the right-hand side of the hefty entrance gate, adjacent to him Neş’et Atay acting as Istanbul correspondent for the Ulus newspaper, offices of the prominent Armenian Newspaper Jamanak, sculptor Dr. Firsek Karol in his studio joining three rooms together, and Andrea Bookstore. This was also where the very first exhibits of the D Group (D Grubu) were held. Visconti, one of Istanbul’s first ready-made garment sellers, and furrier Sanovich are known to have taken up shop in Narmanlı Inn’s smaller spaces. In its later years the building also housed Deniz Bookstore, frequented by university youth and responsible for the flourishing of an important subculture in Beyoğlu.

Here is how Merve Erol explains the significance of Deniz Bookstore in an article he wrote for Zero Istanbul in 2016:

As certain rock clubs, large and small publishing houses, political entities and cultural centers slowly moved to Beyoğlu at the outset of the 1990s, the artistic-cultural-political scene spread out across the city began clustering here. Still, the Tünel quarter had not caught up with this dynamism except for a couple record stores, guitar stores, stamp collection shops and the Tarık Zafer Tunaya Cultural Center – until, that is, the opening of Babylon.

Shareholders first transferred 15 percent of the inn’s equity to the Yapı Kredi Koray group for restoration purposes in 2001. The project was approved by the Council of Monuments in 2002, but the restoration was stalled by the objections of non-governmental organizations and professional chambers and the issuance of a stay of execution. Upon this, 12 heirs of the Narmanlı Inn brought a lawsuit against Koray Group in 2008 and regained their shares. In 2009 the Inn acquired 2nd degree monument status – with the exception of its outer façade. It was later sold to Mehmet Erkul, owner of Erkul Cosmetics, and owner of Eteksan Textiles Tekin Esen for 57 million dollars in 2014. Neighbourhood associations opposed the restoration project proposed by Sinan Genim, the architect contracted by the new proprietors of the inn, but the court rejected the case.

These developments came in parallel to statements made jointly by Beyoğlu Mayor Ahmet Misbah Demircan and Nizam Hışım, Chair of the Association for the Beautification of Beyoğlu regarding the neighbourhood’s gentrification: “We will clean this place up. We don’t want it full of useless crowds of just anyone off the street, but true consumers.” Representatives of neighbourhood associations claim that what has ensued since then is a process of “gentrification”, “elitification” and “depopulation”, followed by a bringing in of its ‘own’ crowd instead.

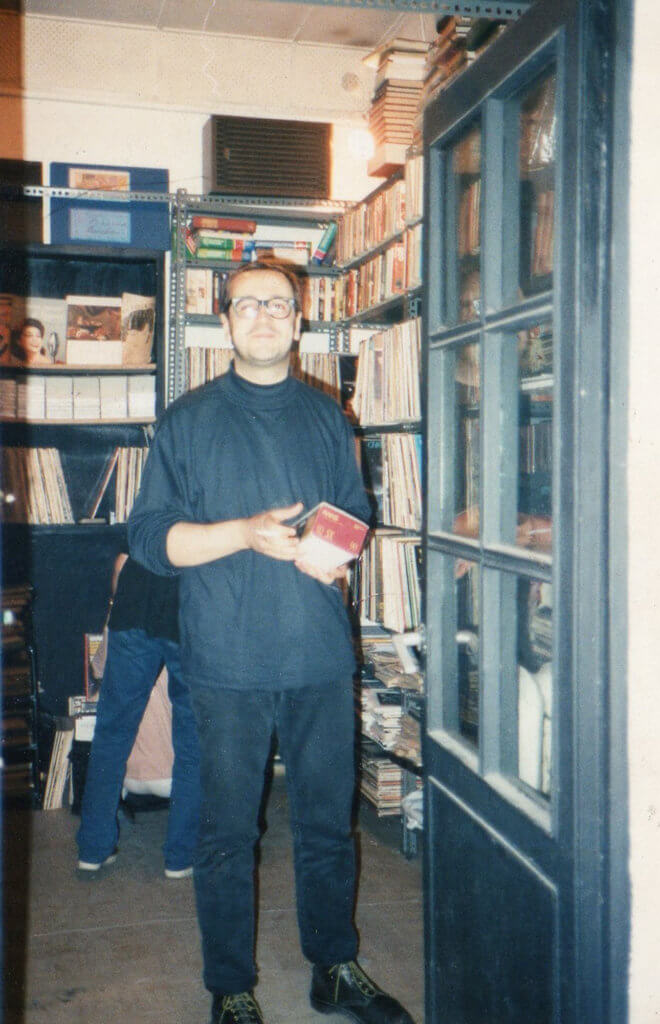

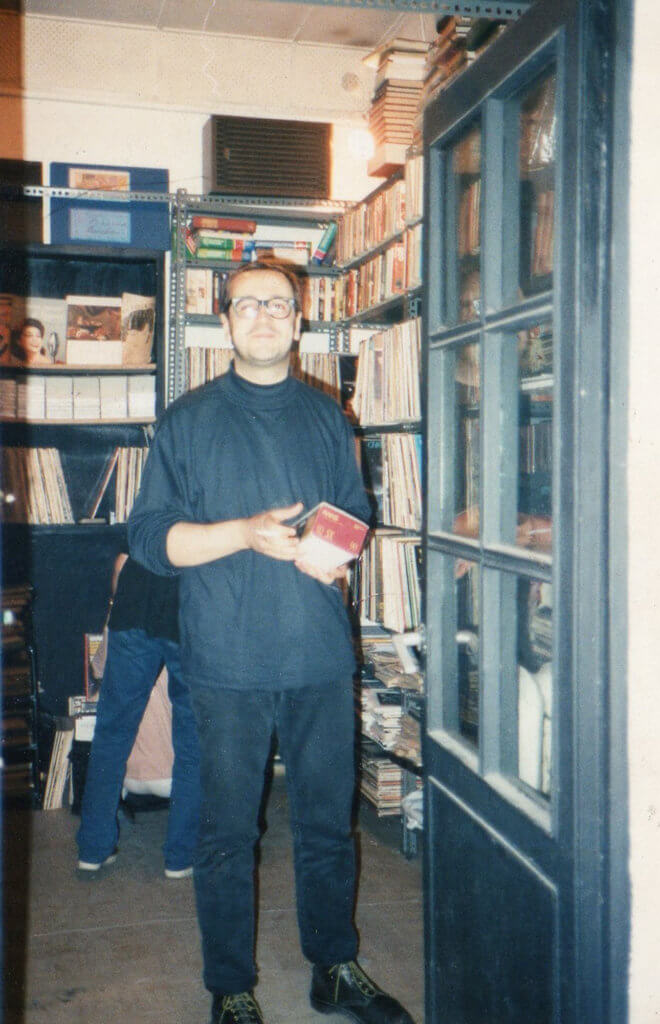

Deniz Bookstore. sinematikyesilcam.com.

Talimhane and the environs of the Open Air Theater (Açıkhava), in the hands of this crass and ephemeral mentality capable of thinking that the problem will be solved simply by carrying a cinema, that managed to survive and remain active over almost a century in a country like Turkey utterly unable to preserve its material memory, to a new location five storeys up.” Quoted from Merve Erol’s “Göçmemiş Kediler: Narmanlı” (“The Cats That Remain: Narmanlı”) article in Zero Istanbul.

Mari Gerekmezyan is among those whose paths crossed Narmanlı Inn, just like many of Istanbul’s artists of her time. The fact that her lover Bedri Rahmi lived here plays an important part in this. Gerekmezyan is among Turkey’s first woman sculptors. Born in Kayseri’s Talas district in 1913, Mari Gerekmezyan completed her elementary education at Vart Basrig Primary School in Kayseri. She later settled in Istanbul and attended the Esayan (also spelled “Yesayan”) High School for Girls. Influenced by Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, whom she came to know at this time, she enrolled in the Philosophy Department of the Istanbul University Faculty of Literature and graduated in 1943. She taught art and Armenian at the Istanbul Getronagan and Esayan High Schools.

Later on, she became a guest student at the Department of Sculpture in the Academy of Fine Arts and developed a romantic relationship with Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu, who was an assistant there. It is believed that Bedri Rahmi wrote his famous poem Blackberry (Karadut) for her. Granted the Ankara Sculpture Exhibit Award for her busts of Prof. Neşet Ömer and Prof. Şekip Tunç in 1943, and the First Place Prize in the Ankara State Fine Arts Exhibit for her bronze bust of Poet Yahya Kemal Beyatlı in 1945, Gerekmezyan produced works considered successful in terms of their verisimilitude and the expressions she captured, and deemed out of the ordinary for their time – some of which have gone missing. Her limited number of registered works, on the other hand, are known to be in the Istanbul and Ankara Painting and Sculpture Museums, while the bust of Bedri Rahmi is in the private collection of the Eyüboğlu family.

Editor Sevengül Sönmez of Bilgi University characterized Gerekmezyan in her remarks to Hürriyet Daily News on the occasion of a memorial exhibit held in her name in the Istanbul Getronagan Armenian High School in 2012 as “Turkey’s first female sculptor, overshadowed by Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu for being very young and yet at the start of her artistic career.” Gerekmezyan was shunned by her own relatives and art circles alike due to her Armenian identity on the one hand and her relationship with Bedri Rahmi, a married man, on the other. Writer Karin Karakaşlı describes this based on her research on Gerekmezyan as her “ethnic and artistic ostracization”. In her story Sabır Taşı (The Patience Stone), where Gerekmezyan is featured as the main protagonist, Karakaşlı also writes that Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu’s friend Fred Gross married her even though he knew about their relationship, in order to put an end to rumours.

Frequently featuring in many of Bedri Rahmi’s portraits herself, Gerekmezyan died of tuberculosis in 1947. Her grave currently rests in the Şişli Armenian Cemetery.

One of Turkey’s first etching and engraving artists, painter Aliye Berger’s upper floor studio in Narmanlı Inn, gently decaying at the time, was a regular haunt of the writers, artists and intellectual circles of Istanbul in the 1950s and 60s. Achieving renown for the first time upon receiving the first place prize in a painting contest held by Yapı Kredi Bank in 1994, the artist came to be known for her expressionist engravings.

Aliye Berger was a member of the Şakir Pasha family, as the sister of famed painter and writer Cevat Şakir Kabaağaçlı – widely known as the Fisherman of Halicarnassus – and painter Fahrelnisa Zeid, as well as aunt of the first female ceramics artist Füreya Koral, actress and play director Şirin Devrim and painter Nejat Devrim. While Şakir Pasha was Governor of Crete in 1890 his brother Ahmed Cevad Pasha had been appointed the grand vizier. The Fisherman of Halicarnassus was born at this time. Yet when Cevad Pasha was dismissed from his post as a grand vizier in 1894, his brother Şahir Pasha also resigned from duty and returned to Istanbul. With the emergence of financial difficulties in 1914, Mehmed Şakir Pasha settled back in the Kabaağaçlı farm in Afyon. During an argument here, Şakir Pasha was shot by a bullet from a gun wielded by his son, 11-year-old Aliye’s elder brother Cevat Şakir Kabaağaçlı, and died. Cevat Şakir was sentenced to 14 years of hard labour. In his youth he was a successful painter. Later on, he made Bodrum, where he was sent on exile, known to the entire world with his works as a writer. He also became the pioneer and promoter of Blue Cruises, which have taken their place among Turkey’s important tourist attractions today.

Aliye Hanım studied at the Notre Dame de Sion French High School. In the wake of Mehmed Şakir Pasha’s death, his wife Sare İsmet Hanım of Crete had taken close interest in her daughters Aliye and Fahrelnisa, and in making sure they received a good education in particular. First taking painting and piano classes, Aliye began learning how to play the violin in 1924. Her violin instructor was the famous Hungarian violin virtuoso Karl Berger, who had participated in Hungary’s popular uprising. Having taken refuge in Istanbul, he was making a living giving violin lessons. Aliye Hanım fell in love with her teacher. In a fit of jealousy one night, she picked up her gun and went pounding at Karl Berger’s door. The virtuoso’s servant opened, upon which Aliye Hanım fired, wounding the servant. She was sentenced to 35 days in prison. It was decided that her statement be postponed on grounds that she had committed this crime in a choleric fit according to doctor reports, and that she belonged to a notable family. Love burgeoned between Karl Berger, moved by this incident, and Aliye Hanım, and a relationship that was to last 23 years began.

Following 23 years full of love, the couple decided to get married and united their lives. Six months after the marriage Karl Berger passed away as a result of a heart attack he had in Büyükada. This loss deeply affected the artist. Aliye Berger had not been able to fully concentrate on painting until then, as much as she had wanted to. In the wake of the death of her husband, she went to London in 1947 and studied sculpture and engraving in John Buckland Wright’s workshop. She returned to Turkey in 1951 with 150 engravings and opened her first personal exhibit at the age of 45.

However, Aliye Berger’s main claim to fame came with her reception of the first place prize with her oil painting Sun Rising (Güneşin Doğuşu) in the “Work and Production” (“İş ve İstihsal) themed contest organized by Yapı Kredi Bank on the occasion of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) congress held in Istanbul in 1954. With most of her works consisting of black-and-white engravings, Aliye Berger held a total of 11 solo exhibits in Turkey and Europe, and participated in 50 national and international group exhibitions.

Sincerity cannot be taught. Neither in life, nor in art. There is no such school. I did as I was… In my works I wanted to reflect my own world, the world as I lived it with all its beauties, pain, loves, losses, with my rebellions and compliances, my hopes and my despair, that which I lived… But what I was most impressed and influenced by was that event we call life, that adventure, embracing this all. And, of course, love.

Aliye Berger

Aliye Berger at her studio/home, SALT Research, Yusuf Taktak Archive.