GALATASARAY SQUARE

Galatasaray Square is an intersection point located almost midway between Taksim and Tünel squares. Meşrutiyet Avenue from the Tepebaşı side and the Boğazkesen Hill from Tophane meet at this crossroads. Though it occupies a relatively small plot of land, its name carries a weight that cannot be measured by its surface area.

Though it takes its name from Galatasaray High School, still located in the square, it owes the special place it has come to hold in the social memory of the last 20 years to the Saturday Mothers, who meet here every Saturday at 12.00. This is why it is also known as the Saturday Square. A variety of rights-based organizations and initiatives as well as political groups protesting violations in different areas also make frequent use of this space. It is for this reason that a throng of police officers is also often present in the square for security purposes. This army is stationed here at times in order to prevent those in the square from marching elsewhere, other times to stop them from gathering in the first place. That is to say, they don’t actually have much to do with people’s security.

Galatasaray Square appears, in this sense, to have stolen the spotlight from Istanbul’s perhaps most political square, Beyazıt, in the post1980s. The fact that rights and identity-based movements marked the period following 1980 may have played a large part in this. The square takes its name from a barracks/school founded in 1481 in this then unpopulated area by Bayezid II in order to train Inner Palace boys/ servants (“içoğlan”). In other words, the structure built here known as the Galata Palace (“Saray”) lent its name to the entire neighbourhood. Today, this school has been replaced by Galatasaray High School. The Galatasaray Hammam (bathhouse) was also built back then for the hygiene of Palace boys studying here and to sober up drunks. The Galatasaray Post Office built in 1875 functioned as one where residents of Istanbul could access postal and phone services in a historic establishment all the way up to the 2000s. The postal affairs (such as protest wires to the Ministry of Justice and of the Interior, or solidarity messages to prisons) of demonstrations held on İstiklal Avenue were also carried out here. The quotidian relationship Istanbul’s residents had with this historic space was cut off with the decision to convert the building into a museum.

The Çiçek (Flower) Passage located across from Galatasaray High is, in a way, a reference to Beyoğlu’s Russian past. Just like Rejans restaurant, it belonged to white Russians migrating to Istanbul in the wake of the October Revolution. It is also possible to map out the alcohol policies of military and civil fascist, conservative administrations from Ottoman times to present by looking at the historic journey of this arcade. Galatasaray Square has, of course, its fair share of passages or arcades, which are a symbol of Ottoman modernization. One particular attribute of these arcades that make the city roamable is that they constitute the first shopping centers of Istanbul run by non-Muslims. Their hand-over to appointed trustees (kayyum) or to the Treasury is, therefore, an example of the Republic’s transfer of capital from non-Muslims to Turks. The square also houses two sculpted monuments in a city generally devoid of these. The stories of Şadi Çalık’s 50th Anniversary of the Republic (Cumhuriyet’in 50. Yılı) and İlhan Koman’s Mediterranean (Akdeniz) are an artistic manifestation of the clash of Islamist and Westernist politics in Turkey. Finally, of course, the tale of the Saturday Mothers – or Saturday People – appears as a historic symbol of state violence and ruthlessness, and of the impunity of state officials, but also of resistance against this, of human rights and the struggle to attain these.

GALATASARAY HIGH SCHOOL

In 1839, the first modern medical school Tıphane and Cerahhane-i Amire (the “Medical and Surgical school”) originally established in Şehzadebaşı moved to a plot of land where, for a couple of centuries, there had been a school raising boys to serve in the Inner Palace. Upon moving here the school took on the name Mekteb-i Tıbbiye-i Adliye-i Şahane (the Imperial School of Medicine). With the fire of 1849, however, the medical school was forced to relocate once more. “Mekteb-i Sultani” (the Imperial School) opened its doors to students here on the 1st of September 1868. This new school teaching in French and Turkish, considered a symbol of Tanzimat (Reorganization) era education, had 172 Muslim and 237 non-Muslim (Armenian, Latin, Greek, Jewish, Bulgarian) students in its early days. A secular school that was to give education in French was met with adverse reaction just as every other innovative step. First of all, international pressures had to be resisted. Russia, apprehensive of the spread of French influence in Ottoman lands, sent a diplomatic note on the matter. Attempts to start a Russian school of similar standing did not, however, succeed. The Pope tried to forbid the enrolment of Catholic students in Galatasaray, but was prevented upon French intervention. The Armenian Catholic Patriarch in Istanbul did, however, end up prohibiting children from his own congregation from being sent here.

Then ensued the ‘domestic and national resistance’. At first, Turkey’s Ministry of Education (Türkiye Maarifi) did not appoint the co-principal of the school for quite a long while – or rather, it withheld the permission necessary to start duty from the already appointed Turkish director. After which the Neo-Ottomans and Namık Kemal stepped in, and the school became the target of nationalist criticism. Greeks1* were displeased by the lack of Greek lessons; Jews were unwilling to send their children to a school run by a Christian principal. The Ottoman Shaykh al-Islam pronounced it against religion for Muslim and Christian youth to study together. Yet none of these were able to stop the school from teaching, for the state needed trained staff with knowledge of foreign languages, and French was still the working language of diplomacy at the time. Levantines, Armenians and Greeks called “dragomans” (interpreters) could speak Latin, Greek, English and certain Balkan languages along with French, and as such had constituted the main pillar of Ottoman Foreign Affairs. The French Revolution of 1789 had, however, impacted all multi-national empires and even nation-states, and the Greek2** war of independence had followed on the heels of that of the Serbs. During this war that lasted eight years, the Ottoman administration in search of scapegoats set its sight on the dragomans and decided that they were leaking information to the Greeks. The curtain thus fell on the era of dragomans in Ottoman Foreign Affairs. This, in turn, made an institution providing education in French a must in Ottoman lands.

Gradually increasing in number, the students of the school founded the Galatasaray Sports Club, the origins of what is now one of Turkey’s three football giants, in 1905. Sustaining severe damage in a fire in February 1907, it took until 1909 for the school’s renovation to be completed. Offering high school education alone up until then, it came to incorporate elementary and middle school education as well in 1908. Graduating 60 students in 1912, this number declined to 18 in 1915, while in 1916 the school produced no graduates whatsoever. Official history explains this as being a result of the conscription and death of students in the Balkan and Çanakkale wars at the time, unsurprisingly failing to make any mention of Armenian Genocide victims studying there.

President of France Charles De Gaulle participated in the school’s centenary celebrations in 1968. It had graduated 4717 students up until that date. Turned into an Anatolian High School in terms of status in 1975, the school was modelled so as to start at an elementary level and continue through the end of university as per an agreement made with France in 1992. In 1993, both the elementary section and Galatasaray University were launched.

GALATASARAY HAMMAM

Stepping out on Turnacıbaşı Street (formerly called Su Terazisi – i.e. “Water Scales”) adjacent to Galatasaray’s wall, one encounters the Zografeion (Zoğrafyon) Greek High School for Boys. This school was endowed to the Istanbul Greek community by banker Christakis Zografos in 1892. Designed by architect Pericles Photiadis (Periklis Fotiadis), it is still active today. Moving past the high school, the Galatasaray Hammam (bathhouse), registered as having been erected in 1715, appears at the end of the street. A facility open to the public, the bathhouse is said to have been in service through the night for those drinking the hours away in Beyoğlu to be able to wash themselves and sober up. The structure lost its architectural authenticity in repairs it underwent in 1965. The bathhouses of Istanbul were also among the sites where the LGBTI+ scene forced underground due to certain prohibitions and barriers in the 1980s and early 1990s could carry on. The Galatasaray Hammam, however, did not play host to such gay gatherings due to its touristic character and expensive rates.

GALATASARAY POST OFFICE

Why aren’t people in Istanbul able to reside in homes or dine in restaurants that date hundreds of years back? Why can’t they take care of business in century-old public buildings? Why can’t children study in schools established centuries ago? Many reasons may be listed here in response, such as the lack of consideration for the historic fabric of a city so significant for its rich history, the inadequacy of protective policies and the fact that they are often violated by the hand of local administrations themselves, the absence of education or effective measures aimed at building awareness of historic heritage and its preservation, and rapid urbanization. The Beyoğlu Post Office is yet another victim of this all. Though preserved as a museum, it has completely lost its original form due to disastrous restorations it underwent.

The edifice that later became the Galatasaray Post Office facing İstiklal Avenue was built by merchant Theodor Sıvacıyan in 1875 as a family residence. The building made of stone, situated upon 340 square meters of land, was composed of a basement, a ground floor, three full floors and a setback attic with a panoramic view of the Bosphorus. Sıvacıyan and family lived in the top floors of this building adorned with doors imported from France and ceiling decorations applied by Italian artists, while its ground floor was occupied by a pharmaceutical lab run by Mr. Apolonatos. In 1907 Hüseyin Hasip Effendi bought the building and made it the Beyoğlu Post & Telegraph Department. The Istanbul Radio continued broadcasting out of rooms on the second floor in 1943-44. There were also British and German radio companies operating here for a while. After sustaining damage in the fire of 1977, it was repaired without remaining true to its original under the austerity measures of the period, and put back in service in 1982. Yet, a short while later, it was decided for the Galatasaray Post Office to be converted into a museum, with the building thus evacuated and the post office temporarily relocated to a building right across upon orders by the General Directorate of Postal Affairs and the Ministry. Restoration work hence began. Following a corruption-ridden restoration process that ended up disputed in court, the historic post office somehow ended up as the Galatasaray Museum. Having grown out of this museum founded by Ali Sami Yen in 1915, the Galatasaray University Culture and Art Center has been operating out of the Historic Beyoğlu Post Office at No: 90 on İstiklal Avenue since the 6th of December 2009.

One of the definitive aspects of the Galatasaray Post Office was that members of rights-based organizations waging various campaigns met here in order to send their protest wires or campaign-related postcards. For instance: During death fasts started in 2000 within prisons against the transition to F-type cells, many lost their lives or compromised their health. The operation conducted by security forces on the 19th of December 2000 became one of the most extreme instances of state violence in prisons. In the aftermath of the 19th of December, women from various women’s groups in Istanbul came together to organize a series of actions around the slogan “We Are Concerned” (“Endişeliyiz”) for detainees in F-type prisons. Carrying out their first protest on the 13th of January by flying balloons that read “We Are Concerned”, these women later met in front of the Galatasaray Post Office at 13.00 on a weekly basis to send letters to women in prisons and make press statements.

Please enter a title attribute

Commissioned by banker Christakis Zografos Effendi to Cleathy Zagno, a famous architect of the time, as a new market building/shopping arcade in the plot of the Naum Theater that burnt down in the 1870 Beyoğlu fire, Çiçek (i.e. “Flower”) Passage is perhaps the first place to come to mind when speaking of Beyoğlu or İstiklal Avenue. Started in 1874 and completed in 1876, the building was called Cite de Pera at the time of its construction. With its main entrance on İstiklal Avenue, the other end of the arcade opens onto Sahne Street, where the Fish Bazaar is located. In the past, the building housed 24 shops and 18 apartments. Japanese toy-maker Nakumara, florist Pandelis, Köleyan’s Hair Salon, Acemyan Tobacconist’s, Teodoradis’ Pharmacy, Yorgo’s (Giorgos) Tavern, Hristos (Christos) Café and Degüstasyon Restaurant were all located in the Çiçek Passage – which corresponded to something of a modern-day shopping mall. In 1908, Küçük (Little) Said Pasha, Grand Vizier to Abdulhamid II, purchased the arcade and moved here the Flower Production and Marketing Cooperative (Çiçek Üretim ve Satış Kooperatifi) that held wholesale flower auctions among other things. The arcade thus came to be known as the “Flower Passage”

Writer İsmail Güzelsoy provides a different account as to why the passage was named as such in his book titled İstanbul’un Gezi Rehberi (A Travel Guide of Istanbul):

“It is known that White Russian girls fleeing from Russia after the October Revolution sold flowers here for quite a while. These poor girls selling flowers to passers-by in front of Galatasaray High School would collectively take refuge in Çiçek Pasajı in order to avoid being harassed by British and French soldiers. This arcade where some male relative or other usually worked as a waiter or cook was therefore naturally a safe haven for these girls.

The arcade takes its name from this unpleasant phase, and not from flower auctions held here as has been claimed.” The arcade’s transformation into a spot for taverns (meyhane) and pubs stretches back to the 1930s. The Degüstasyon Restaurant started placing tables on the interior of the arcade during summer months, and these ended up being much sought after. The shops were then turned into pubs or taverns one by one. In time, this became a site of some of the best taverns in Istanbul along with Krepen (or Crespin) Passage. The arcade’s men-only taverns with music and dance frequented by sailors were called “baloz”. The tradition of drinking with large barrels serving as tables in these “baloz” taverns between florists’ shops was preserved until recently. The arcade took on its current look when the florists were moved to the adjacent street in the 1950s.

In 1978, certain parts of the arcade collapsed. The Mayor of Beyoğlu appointed in the wake of the 1980 military coup imposed military order so as to ‘discipline’ the tables in the passage. In 1988 the arcade was renovated by the municipality. In 2005 its roof was repaired and lighting system ameliorated. The arcade still serves as a hub of taverns and pubs today, catering mostly to tourists. It survives at present as part of a protected quarter of taverns in Istanbul along with Nevizade, in this port town famed for its taverns since the Byzantine era.

Please enter a title attribute

When the Naum Theater and Jardin de Fleurs Hotel (which is where the first circus show in Istanbul was held in 1856) located between two streets leading onto İstiklal Avenue burned down in 1870, this arcade in the form of a long corridor connecting the streets was built instead. Commissioned by Onnik Düz, its architect was Pulgher. The 56-meter- long corridor-type arcade had a glass ceiling. Each of the 22 shops located in it had a room upstairs as well as a kitchen and cellar. The structure was built in the neo-Renaissance style, with the stones used in the façade brought from Malta.

Residents of Istanbul also called the arcade “Aynalı (Mirrored) Passage” due to the human-sized mirrors installed on the main supports in order to visually augment the space. The arched double windows located between sculptures within niches on the upper level and columns with Corinthian capitals were the other notable decorative elements in the arcade. Additionally, the outer doors were ornamented with rosettes, one bearing an embossed lion head and the other a relief of Ataturk’s face. When it was first opened, Hairdressers Karkonakis, Massali and Zografos, tailor Konstantin (Constantine) Hisar, Madame Rizzo and Marko Perpignai, silk thread (ibrişim) seller Emmanuel Karlatos and Yorgo Tsiotis, thread-seller Josef Miari, watch-seller Wosterling and florist Sabuncakis had stores here. Handed over to the Treasury in 1929, the arcade was sold off by the Emlak and Eytam (Real Estate and Orphans) Bank.

ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCES

In 1995, during Tansu Çiller’s prime ministry, Doğan Güreş passed on the post of Chief of General Staff, which he had held from 1990 to 1994, to İsmail Hakkı Karadayı. At this time Kurdish provinces were known as the “OHAL” or state of emergency region. “Irregular warfare” had been adopted as a strategy in the army’s fight with the PKK, the Turkish Armed Forces had been restructured in accordance with the “low-intensity warfare” concept, and the Office of Special Warfare (Özel Harp Dairesi) had already taken on the name of “Special Forces Command” (Özel Kuvvetler Komutanlığı). The number of village guards was increasing by the year. As of 1993, a special security strategy was put in motion by then Prime Minister Tansu Çiller and Chief of General Staff Doğan Güreş’s team in line with the concept of “Territorial Dominance and Preventing the PKK from Existing in the Area”. What this strategy entailed for the civilian population was the forced evacuation of villages and other residential areas, as well as the gradually mounting number of “perpetrator-unknown killings” and forced migrations.

While those made to disappear between 1980 and 1990 numbered 22; according to figures verified by the Memory Center, this number reached 81 in 1993 and 202 in 1994. A great majority of those disappeared were inhabitants of the Kurdish populated cities due to the strategy of irregular warfare implemented here. The provincial distribution of the 500 corroborated by the Memory Center out of the 1300 people believed to have been disappeared in Turkey up to date since the military coup of September 12, 1980, is as follows: Şırnak – 135, Diyarbakır – 123, Mardin – 65, Hakkari – 45, Batman – 26, Istanbul – 26, Şanlıurfa – 13, Tunceli – 11, Bitlis – 10, Ankara – 7, Other – 39.

This reality brought the Human Rights Association (İnsan Hakları Derneği) to organize its first campaign on enforced disappearances in 1992. Three years later, in 1995, the Human Rights Association and Human Rights Foundation (İnsan Hakları Vakfı) jointly embarked on a larger-scale campaign. The notion of ‘enforced disappearances’ became widely known as ‘disappearances under detention’.

Saturday Mothers

On the 15th of May 1995 the body of Hasan Ocak, disappeared under police custody 58 days ago, was identified by his family at the Forensic Medicine Institute. During the period of his disappearance, his friends and family had undertaken many actions demanding that he be found immediately, had asked after the fate of Hasan Ocak, and kept public attention focused on this case.

Hasan Ocak’s arrest occurred right after the days known as the “Gazi Incidents”, when three coffeehouses and a workplace in Istanbul’s Gazi neighbourhood heavily populated by Alevis, were simultaneously raked with gunfire by unidentified persons. Villagers caught sight of Ocak’s lifeless body five days after his arrest, on the 26th of March 1995, in Dedeler close to the Beykoz Buzhane Village. They notified the gendarmerie, upon which the matter came to the attention of the Beykoz Public Prosecutor’s Office. Fingerprints and blood samples were taken along with photographs. These fingerprints were relayed to the Istanbul Police Department and its district stations. However, despite being searched for all over Istanbul, Ocak somehow could not be identified with the evidence at hand.

His family finally identified Hasan on the 15th of May 1995 through the records of the Forensic Medicine Institute. Though his cause of death was strangulation by wire or string, his face had been mangled to prevent recognition and there were marks of torture all over his body. The family announced, with recourse to witnesses as well, that Hasan Ocak had last been seen at the offices of the Counter-Terrorism Unit. The autopsy report also revealed that Ocak had been choked to death. The criminal complaints filed by the family were of no consequence; the perpetrators remained undetermined. When it became apparent that Rıdvan Karakoç and Ayşenur Şimşek too had been disappeared as the search for Hasan Ocak’s body was yet ongoing, rights defenders from the Human Rights Association gathered and sat at Galatasaray Square both in order to prevent the continuation of enforced disappearances and for the identities of perpetrators to be revealed. They began silently repeating this action every Saturday in the same place at the same time. Their source of inspiration was the Plaza de Mayo protests of relatives of those disappeared under the junta regime in Argentina.

After a certain while, however, police interventions began. The police- owned “Bus of the Disappeared” (“Kayıplar Otobüsü”) dubbed as such by the Police Department started parking right next to the protestors and making announcements, saying that nobody had been disappeared under detention, and that those claimed to be lost had, in fact, joined illegal organizations. Families were called on to cooperate with the state. Sometime later the police began arresting everyone who came to Galatasaray Square around noon on Saturdays. The sit-ins were paused as of the 13th of March 1999, and this break lasted until 2009. They were resumed on the 31st of January 2009 with the start of Ergenekon arrests and the preparation of the indictment in this case. The possibility of putting soldiers responsible for enforced disappearances on trial had created hope. On the 29th of January 2011, Saturday protests began in Cizre as well. The court case brought against Colonel Cemal Temizöz considered responsible for massacres and disappearances in the region was influential in instigating this. Prime Minister at the time, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan met with the Saturday mothers in 2011 and heard their demands. The relatives of the disappeared continued their Saturday sit-ins in Istanbul, Diyarbakır, Batman and Cizre until the coup attempt of July 15, 2016. Held in Istanbul alone after this date, the protest was met with police violence on the 25th of August 2018, its 700th week, upon orders by Minister of the Interior Süleyman Soylu based on “terrorism” charges, and 47 of the group of relatives of the disappeared and human rights defenders were arrested.

Films, books and songs on the disappeared

A selection of films, documentaries, literary and musical works from across the world on enforced disappearances systematically perpetrated in over 70 countries, focusing on the stories of the disappeared.

FİLMLER

Missing (1982), Director: Costa-Gavras, ABD – La noche de los Lápices/Night of the Pencils (1986), Director: Héctor Olivera, Arjantin – La Historia Oficial/The Official Story (1985), Director: Luis Puenzo, Arjantin – Un Muro de Silencio/A Wall of Sience (1993), Director: Lita Stantic, Arjantin – La muerte y la doncella/Death and the Maiden (1994), Director: Roman Polanski, US, UK, France– The Disappearance of Garcia Lorca (1997), Director: Marcos Zurinaga, Spain, US – Imagining Argentina (2003), Director: Christopher Hampton, Spain, UK, US – O Ano em Que Meus Pais Saíram de Férias /The Year My Parents Went to Vacation (2006), Director: Cao Hamburger, Brazil – Rendition (2007), Director: Gavin Hood, US – Dukot/Captured (2009), Director: Joel Lamangan, the Philippines – The Simpsons, 12th Season, 6th episode: The Computer Wore Menace Shoes (2000), Director: Mark Kirkland, US – Infancia Clandestina/Clandestine Childhood (2011), Director: Benjamin Avila, Argentina, Spain, Brazil – Das Lied in Mir/ The Day I Was Not Born (2011), Director: Florian Cossen, Germany, Argentina.

DOCUMENTARIES

Ormancik (2014), Stêrk TV, Kurdistan – Berxwedana 33 Salan-Dayika Berfo/33 Years of Resistance, Mother Berfo (2014), Director: Veysi Altay, Turkey – Bûka Baranê (2013), Director: Dilek Gökçin, Turkey – Sabah Yıldızı: Sabahattin Ali/The Morning Star: Sabahattin Ali (2012), Director: Metin Avdaç, Turkey Nuestros Desaparecidos/Our Disappeared (2008), Director: Juan Mandelbaum, Argentina – Nostalgia de la Luz/Nostalgia for the Light (2010), Director: Patricio Guzman, France, Germany, Chile, Spain, US – El Botón de Nácar/The Pearl Button (2015), Director: Patricio Guzman, Chile.

LITERATURE

Catch-22 (1961), Written by: Joseph Heller – Darkness at Noon (1940), Written by: Arthur Koestler – The Disappeared (2009) Written by: Kim Echlin – “Graffiti” from the book Queremos tanto a Glenda/We love Glenda so much and other tales (1980), Written by: Julio Cortázar – Información para extranjeros/Information for foreigners (1995), Written by: Griselda Gambaro – When Darkness Falls (2007), Written by: James Grippando – La muerte y la doncella/Death and the Maiden (1991), Written by: Ariel Dorfman – The Ministry of Special Cases (2007), Written by: Nathan Englander – Mi hija Dagmar/My Daughter Dagmar (1984), Written by: Hagelin Ragmar – Widows (1981), Written by: Ariel Dorfman – Feeding on Dreams: Confessions of an Unrepentant Exile (2011), Written by: Ariel Dorfman – José (1987), Written by: Matilde Herrera – Dirty Secrets, Dirty Wars: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1976-83: The Exile of Editor Robert J. Cox (2008), Written by: David Cox.

POPULER MUSIC

Hay Una Mujer Desaparecida, Holly Near (with Barbara Higbie) – Desaparecidos, Little Steven & the Disciples of Soul – Desapariciones, Rubén Blades, Mothers of the Disappeared, U2 – They Dance Alone, Sting – The Circle, Kris Kristofferson – Undercover of the Night, The Rolling Stones – Cumartesi Türküsü/Saturday Ballad, Sezen Aksu – Beni Bul Anne/Find Me Mother, Ahmet Kaya – Benim Annem Cumartesi/My Mother a Saturday, Bandista.

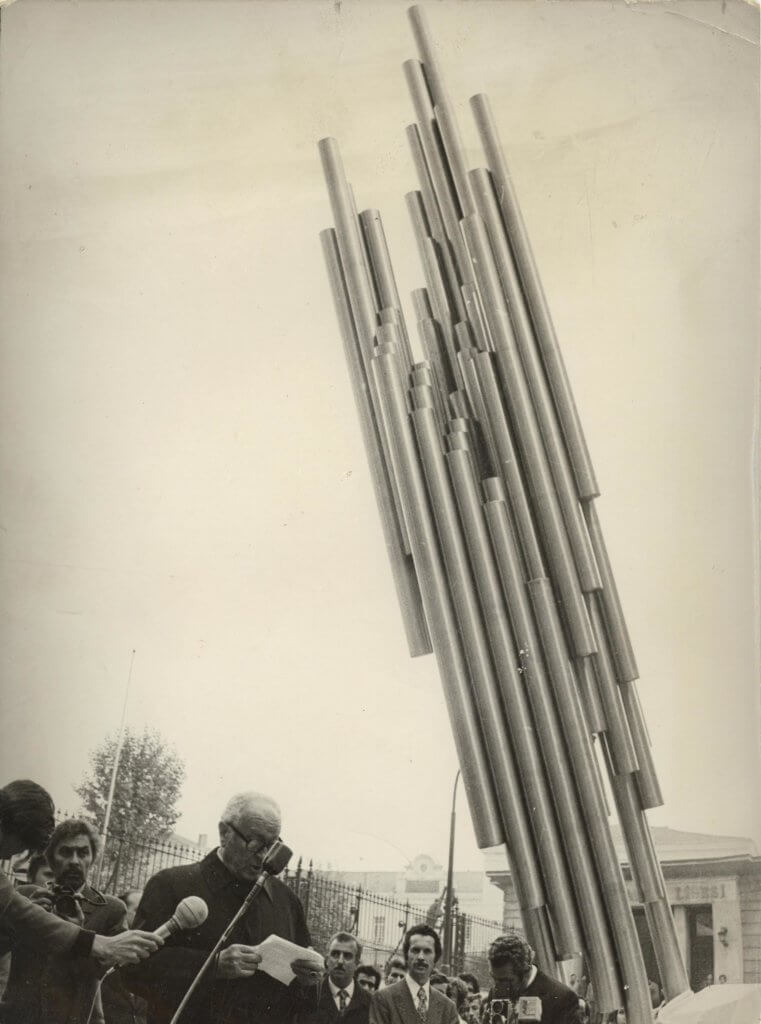

KOMAN AND ÇALIK

Another striking feature of Galatasaray Square is its acting host to two monuments in a city generally devoid of these – the first of which is the monument commissioned to Mehmet Şadi Çalık on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Republic and placed in Galatasaray Square. Consisting of 50 tubes pointing skyward, the sculpture alludes to the industrializing, developing and modernizing character of the Republic. Born in Crete’s Candia district, Çalık is among Turkey’s pioneering abstract sculptors. He is known to have received training from and been influenced by Germany’s first abstract sculptor Rudolf Belling. Belling was one of the German scholars who came to Turkey to escape Nazi persecution. As is known, in the general elections held on the 5th of March 1933, five days after the German Parliament was burnt down by Nazis, the Nazi Party received 43.9 percent of the vote. The Hitler regime established its majority government arresting communist members of parliament, and began governing the country by way of executive orders or decrees. One of its first deeds was purging the universities of anti-Nazi and Jewish scholars. 3100 were dismissed from universities, with their diplomas annulled. At this time university reforms were underway in Turkey, and finding the necessary academics to serve in the newly established universities, as well as those yet to be established, proved near impossible. 42 Jewish professors – 38 of whom were of distinguished standing – arriving in Istanbul fleeing Nazi persecution were thus entrusted with the establishment of Istanbul University. After Istanbul University was opened in 1933, around 300 German scholars came to Istanbul. 70 of these took up posts in the medical school and in hospitals. Later on, German and Austria scholars were also assigned duties at Ankara University. A total of 500- 600 German scholars, including distinguished professors, professors, associate professors, assistants, lecturers and auxiliary academic staff forced to leave Germany after 1933, sought asylum in Turkey with their families. These made important contributions both in terms of the establishment of universities in Turkey and the training of new academics for them. Another dimension of this affair is that it served to fill in the void created by the purge of 93 academics from the Darülfunun, which lost its independence and was shut down with the university reform of 1933 that aimed to bring universities under the control of the single-party regime.

Mediterranean

The second monumental sculpture populating Galatasaray Square is İlhan Koman’s “Mediterranean” (“Akdeniz”) mounted in the Yapı Kredi building after its renovation in 2017, in a manner visible from the street. It is said that this woman figure with two arms spread wide open was initially designed for a slope facing the Mediterranean sea, but when it turned out that it would be placed in front of the Halk Sigorta building (an insurance company later to become ‘Yapı Kredi Sigorta’) in Istanbul’s Zincirlikuyu area, İlhan Koman was asked to downsize his original plans so as not to block out the building’s façade.

İlhan Koman describes his Mediterranean sculpture in the following words:

Each one of the one hundred and twenty pieces composing this design symbolizes a different one of the human communities inhabiting the surroundings of this inner sea, leading different lives, speaking different tongues, and worshipping different Gods. When they all come together in harmony, they form the Mediterranean.

Sitting in front of the insurance company headquarters in Zincirlikuyu Square as of the 1980s, the sculpture was vandalized in 2014 by a crowded mob protesting before the Israeli Consulate located in the same building. Part of the sculpture was hence broken. After being repaired, it was put on display in 2017 on the upper floor of the Yapı Kredi building at Galatasaray Square, in a manner visible from the street.

ŞAHİNYAN AND GÜLER

Also located in Galatasaray Square was the studio Foto Galatasaray belonging to Maryam Şahinyan, a rare example of a woman who rose to prominence in the field of photography in the Ottoman era. Maryam was born in 1911 as the granddaughter of Agop Şahinyan Pasha, representative of Sivas in the first Ottoman Parliament. Coming to Istanbul in order to escape the carnage of 1915, her family became partners of the photography studio, Foto Galatasaray, in 1933; and Maryam Şahinyan began managing the studio independently as of 1937. By the time she handed over her studio due to old age in 1985, she left behind one of Istanbul’s comprehensive physical archives composed of approximately 200 thousand images all in the form of black-and-white negatives and glass plate negatives. Maryam Şahinyan died in 1996.

Turkey’s perhaps most famous and most internationally-known photographer Ara Güler, who passed away on October 17, 2018 was also born in Beyoğlu in 1928. Güler may be characterized as a photographer documenting Istanbul. Starting his career as a journalist in 1950, Güler later became chief of the photography department of Hayat Magazine (Hayat Dergisi), and regional representative of Time-Life and Paris Match. His photographs were exhibited all over the world and published in numerous photographic books. His works were included in private collections, as well as in the archives of the Bibliotheque Nationale de France (National Library of France) in Paris, George Eastman Museum in Manchester, and museums in Cologne and Nebraska. Ara Güler’s photographs may also be seen in Ara Café, opened in 2001 on the ground floor of his studio right by Galatasaray Square.

FATHER ROSE (GÜL BABA)

Rumour has it that Galatasaray Square and the school established here owe their existence to a Bektashi dervish by the name of Father Rose. At least this is what Evliya Çelebi’s Book of Travels says. According to legend, Sultan Bayezid II, the successor of Mehmed the Conqueror, was returning from a hunt one day when he was drawn to the sweet fragrance of flowers and thus ended up visiting Father Rose, a true lover of nature who had covered in rose gardens the slopes on which Galatasaray is now located. During this visit Father Rose asked the sultan to have a school built in this place; and, as the sultan took his leave, presented him with two bouquets of roses – one yellow and one red. This is where Galatasaray’s colours are said to have come from. Father Rose fought in many wars from the time of Mehmed the Conqueror to that of Suleiman the Magnificent. He took part in the conquest of Budin, and died during the campaign. His shrine built in 1548 by Governor of Budin Mehmed Pasha is currently located in the center of Hungary’s capital, Budapest.