One of the first that comes to mind among inns left from Ottoman times in Istanbul, the magnificent Sansaryan, takes its name from Mıgırdiç Sanasaryan who commissioned the building to architect Hovsep Aznavur in 1895. It is for this reason that the actual name of this inn is “Sanasaryan” rather than Sansaryan. Hovsep Aznavur is also the architect of the world’s first prefabricated iron structure. Only one of the two structures of this kind he built – the first one – still stands today, and that is the Bulgarian St. Stephen (Sveti Stefan) Church, known as “the Bulgarian Church”, which opened to worship in 1898 in Istanbul’s Balat neighbourhood.

Sanasaryan Inn appears in the records of the Istanbul Governorate as a stone masonry building on Hamidiye Avenue in Sirkeci facing Mimar Kemalettin Street initially built of stone in the neoclassical style with an inner courtyard and six storeys including a basement. The General Directorate of Foundations rented out the building through a tender in July 2013 without waiting for the court process to be completed regarding the ownership and use of the inn. The tender was won in return for 235,000 liras per month by the Özgeylani Construction Company, which was to reopen it as a hotel after an 18-month-long restoration process. At the end of February 2018, however, the Court of Appeals decided to accept the case filed for the return of the title deed of Sanasaryan Inn to the Armenian Patriarchate. As such, the case will be sent back to the court of first instance for a retrial.

Used as the General Directorate of Foundations and the Istanbul Police Headquarters for many long years, the building also served the Civil Courts of the Istanbul Judiciary later on. Sanasaryan Inn owes its notoriety to the torture and abuse inflicted here during its time as the Police Headquarters on members of the Communist Party of Turkey, nationalists and trans people as they were held in police custody. Yet it is also in the spotlight for yet another silenced and obfuscated period and practice of Turkey’s recent history: the matter of properties confiscated from the Armenian citizens of the Ottoman Empire during the 1915 Armenian Genocide and the ongoing issue of returning the seized assets of minority religious foundations to their original owners.

Mıgırdiç Sanasaryan, after whom the building is named, bought the land from Circassian İsmailpashazade İhsan Bey in return for 19,000 Ottoman gold coins in 1889. Sanasaryan was born in 1818 in Tbilisi, where his father Sarkis Sanasaryan, a native of Van, and his mother Mariam sister of Van-based merchant Kevork Seyran had migrated in order to escape Ottoman repression against Armenians. Mıgırdiç completed the Nersesyan School in Tbilisi and set out for Venice in order to continue his schooling at the Surp Ghazar Monastery. Yet, upon receiving news of his father’s death while on the way, turned back from Erzurum. He joined the army at a young age and served the Russian army until 1845. Not only was he decorated with medals due to his success here, but he also received a hefty monetary award.

The rest of Sanasaryan’s story is recounted as follows in a piece written by Zakarya Mildanoğlu for Agos in 2014: “Migrating from Tbilisi to Petersburg, Mıgırdiç Sanasaryan pushed open the doors of Russian capitalism with the entrepreneurial spirit he inherited from his father. He bought a large part of the shares of the Caucasian Mercury Shipping Company (Kafkas Mercury Gemi Şirketi). The good relations he built with other shareholders carried him all the way to the CEO seat. In 1889 the company celebrated Sanasaryan’s jubilee after 25 years of service, and named a ship Mıgırdiç Sanasaryan after him. Sanasaryan made quite a fortune in business throughout his life and devoted part of his wealth to charity work. His home in Petersburg became a haven for Armenian and Georgian students. Left yearning for an education in his own youth, Mıgırdiç Sanasaryan made the educational life of Armenian society his top priority, and never turned down any student asking for financial assistance. Establishing a relationship with progressive figures in Petersburg, he aimed to spread the Russian education system and contemporary developments in the European educational scene across Western Armenia. He wished to extend the opportunities Armenians living in settlements closer to Europe, such as Istanbul, had in terms of theater, literature and music to provincial areas with lower levels of education. For this and such reasons he endeavoured to found a school in a center heavily populated by Armenians in Western Armenia.”

In 1881 Mıgırdiç Sanasaryan established a school by the name of Sanasaryan in Erzurum. He had bought the inn in Sirkeci in order to generate income for this school. His aim was to contribute to the education of orphaned and poor Armenian children. The Sanasaryan Foundation was founded along with the purchase of the inn. In the register of the Armenian Patriarchate there is record of the inn’s title deed belonging to 1909. The school in Erzurum was later shut down and the inn confiscated due to the great calamity of 1915. This school was where the Erzurum Congress gathered on the 23rd of July 1919. It suffered a fire in 1924, and was used as a primary school after being repaired. In 1960, it opened its doors as the Atatürk and Erzurum Congress Museum (Atatürk ve Erzurum Kongresi Müzesi). Today the building serves the public as the Museum of Erzurum Congress and Turkish War of National Independence (Erzurum Millî Mücadele ve Kongre Müzesi).

After the Ottoman Empire confiscated Sanasaryan Inn in 1915, the Armenian Patriarchate was given back control of its revenues only in 1920. In 1928, however, the Special Provincial Administration (İdare-i Hususiye) under the Istanbul Governor’s Office seized control of these revenues once again, and fully nationalized the inn transferring it to the State Treasury. The lawsuit filed by Patriarch Mesrob Naroyan against this ended in 1932 in favour of the Patriarch, and the Patriarchate was thus able to manage the inn’s revenues for three more years. Yet when another lawsuit filed by the Special Administration ended in a verdict unfavourable to the Patriarchate in 1935, the inn first became the Directorate General of Foundations, and was then used as the Provincial Police Headquarters and the Sirkeci Courthouse.

THE NOTORIOUS COFFIN CELLS (TABUTLUK)

During its years as the Istanbul Police Headquarters, Sanasaryan Inn came to be known with the torture inflicted here on leftists and Turkish nationalists of the time and the “coffin” cells where they were kept under detention. The officials of this period were Istanbul Chief of Police Nihad Haluk Pepeyi, his Deputy and Department Chief Selahattin Korkud, as well as Ahmet Demir, Deputy Chief of Istanbul Police who was to become Chief after Pepeyi. Ahmet Demir is held responsible for torturing both Turkish nationalists (also known as ‘Turkists’), and leftists and communists. The reason Chief Nihad Haluk Pepeyi of the Istanbul Police holds signifance is, according to Rıfat N. Bali, the fact that during a visit to Nazi Germany in order to tour the arms factories there with his deputy Korkut, he requested and was permitted to visit the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp: “According to the Jews of Istanbul the only purpose for Haluk Pepeyi’s visit to Germany was his wish to observe first-hand the gas chambers/human furnaces built by the Nazis in order to carry out the Holocaust, and set up similar facilities in Turkey.” Though it was widely rumoured among Turkey’s Jews in particular that such furnaces had indeed been set up in Balat and İzmir, there has been no factual evidence supporting this up to date.

The Wealth Tax was enacted a week after Pepeyi was appointed Chief of Police in Istanbul, and many Jews whether poor or rich, as well as other minority community members, were forcibly sent to labour camps in Aşkale, Erzurum, with a great majority of their possessions seized through the imposition of overly high taxes. Pepeyi’s visit in question to Germany and the concentration camp took place a year later, in February 1943. This visit gave rise to yet another rumour in the country. It was alleged that a request had been made for the return of the remains of Talat (also: Talaat) Pasha, who had been killed in Berlin and was part of the Union and Progress triumvirate, considered architects of the Armenian Genocide, along with Enver Pasha and Cemal Pasha. The body of Talat Pasha, assassinated in Berlin on the 15th of March 1921 by Soghomon Tehlirian as part of “Operation Nemesis” believed to have been a plan for the elimination of the Union and Progress leadership, was transported to Istanbul in 1943 after this visit upon decree by the Council of Ministers, and re-interred in the Şişli Abide-i Hürriyet cemetery.

As a result of the operation responding to the developments starting with an open letter by Nihal Atsız addressing Prime Minister Şükrü Saraçoğlu on the 19th of May 1944, Zeki Velidi Togan, Said Bilgiç, Orhan Şaik Gökyay and Reha Oğuz Türkkan were arrested, held in the coffin cells of Sanasaryan Inn, subjected to maltreatment and torture. In 1946, it was Aziz Nesin and Sabahattin Ali’s turn for torture and time in coffin cells. Among the other guests of the building in this period are Nazım Hikmet, Vedat Türkali, Ece Ayhan, Atilla İlhan, Mihri Belli, Nuri İyem, Hasan Basri Alp, Vartan İhmalyan, Ahmet Arif, İlhan Selçuk, and Ruhi Su, as well as Cihan Alptekin and Ömer Ayna from the revolutionaries of ‘68.

We are able to garner from Sabahattin Ali’s petition for a criminal complaint to the No.1 Martial Law Court dated November 26, 1945, that teacher Hasan Basri Alp was tortured to death in this building in 1945. According to the Police, Hasan Basri Alp had “escaped and run up to the roof, and then fallen to his death”. Writer Vedat Türkali also dedicated his novel Güven (Trust) published in 2015 to him with the following words: “In the noble memory of valiant revolutionary Hasan Basri Alp, a young, very young man who lost his life with dignity on the 27th of January 1945 during a security investigation in Sanasaryan Inn.”

‘Falling from the roof’ later became “jumping or falling out of windows” of police stations in Istanbul in particular for those arrested after the 12th of March and 12th of September military coups. According to witness testimonies the coffin cells in Sanasaryan Inn were taken down in 1947.

Number 19 and 20 are infamous coffin cells. Their width is 60 centimeters, depth 40, and height 180 centimeters. Those put in here are left devoid of sleep, hungry and thirsty. Of the 35 cells only six have tiny apertures, the others are also deprived of air… Many of us were subjected to the torture of being kept in these coffin cells.

Quoted from Sabahattin Ali’s afore-mentioned petition.

ON NEWSPAPER PHOTOGRAPHS

Nazım Hikmet wrote his poem Gazete Fotoğrafları Üstüne (On Newspaper Photographs) in 1959, on the torture and “coffin” cells, in which suspects and detainees were held, in the Police Department in Sanasaryan Inn:

The Chief of Police

The sun gapes like a wound in the sky

Bleeding out.

At the airport.

There waiting to welcome, hands on belly:

Batons and jeeps

Prison walls, police halls

And ropes dangling from gallows

And plainclothes cops invisible to the eye

And a kid tortured could take it no more

Cast himself from the Station’s third floor.

And here comes mister Chief of Police sir

Stepping off the plane

Back from America

For work purposes.

There they studied how to keep from sleep

And quite pleased they were

With electrodes attached to testicles

And lecturing on our very own coffin cells

They explained the benefits

Of putting boiling eggs under armpits

Of lighting a match to and peeling off neck skin bit by bit.

Mister Police Chief steps of the plane.

Back from America

And batons and jeeps

And ropes dangling from gallows

All rejoice that Master is back.

Nazım Hikmet (1959)

THE ARRESTS OF 1951

As Turkey’s NATO membership was approved and soldiers were hence deployed to Korea, the government embarked on a communist hunt within the country. On the 26th of October 1951 teams under the First Department of the Istanbul Police made preparations to arrest the “short-haired lady” at the Galata Pier. This figure called “short-haired lady” in police surveillance reports was, in fact, Sevim Tarı. Having arrived in Istanbul a month ago in a plane from Paris, she was to leave for Marseilles in a ship docking at Galata Pier. She was a medical doctor, and the daughter of former police chief İsmail Hakkı Bey. Her grandfather was Rıza Kalkavan, ship-owner from Rize. In other words, she was no ordinary type. According to police records, she was Foreign Bureau Secretary of the Communist Party of Turkey. She was arrested just as she was about to board the ship, and taken to Sanasaryan Inn. It was claimed that 36 pages of published material belonging to the party were found on her. These 36 pages comprised information on the party program and organization of the Communisty Party of Turkey as well as certain notes. With this operation, the start was given for a series of arrests that began in 1951 but would continue into 1952. Communist Party Central Committee Members Dr. Şefik Hüsnü Değmer, Zeki Baştımar, Reşat Fuat Baraner, Mehmet Bozışık, Halil Yalçınkaya and Mihri Belli were arrested one after the other. This was the most comprehensive wave of arrests that had yet taken place: 187 people were taken under police custody and put on trial in the Ankara Military Criminal Court. The Democrat Party issued a special decree while arrests were ongoing, saying that “there were soldiers as well” among the membership of the Communist Party of Turkey, transforming the “Istanbul Police First (Political) Department cells” in Sanasaryan Inn into the “Ankara Garrison Command No.2 Military Prison and Detention Facility”. All detainees were brought here. Interrogations under heavy torture (as a result of which 16 detainees are said to have lost their minds) were carried out by police officers of the Communist Desk and military interrogators. Interrogations took two years and the court case lasted a year after the investigation was complete, ending on the 17th of October 1954, with 118 people sentenced from one to ten years in prison and to an additional one to three years in exile. Among those involved in the case were names that would later achieve prominence in the literary or political arena: Enver Gökçe, Mübeccel Kıray, Arif Damar, Ruhi Su, İlhan Başgöz, Orhan Suda, Halim Spatar, Behice Boran, Şükran Kurdakul, Nejat Özön, Vedat Türkali (Abdülkadir Demirkan), Ahmet Arif, Arslan Kaynardağ, Kemal Bekir, Muzaffer Arabul, Selçuk Uraz, and Sadun Aren.

SANASARYAN INN AND LGBTİ+S

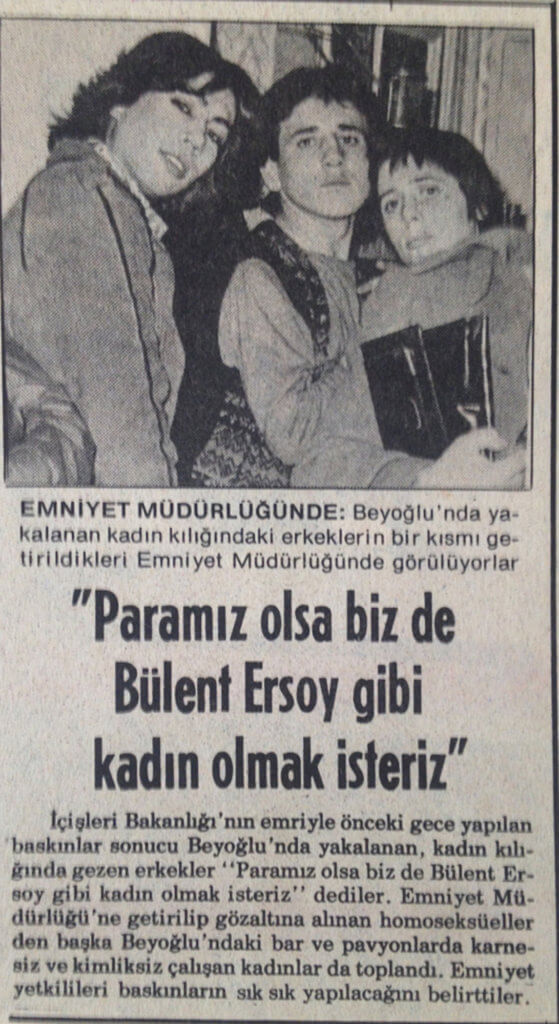

Nationalists, communists and revolutionaries were not the only victims of this Police Directorate building, where dissenters were kept and subjected to interrogations involving beating and torture prior to the military coup of September 12. Especially in the period between the two military coups of the 12th of March 1971 and 12th of September 1980, trans people too suffered their share of the brutal despotic practices of the day along with revolutionaries.

Once, it was 1977 or 78, we 35 trans people wrought havoc in Sanasaryan Inn… We formed a human chain, went up all the way to the attic, where the dome was… Right then we noticed the iron cabinets used for storing files were padlocked. We said, ‘What are you keeping in there, why are they locked up like this?’ They said there were ‘terrorists inside’. We exclaimed, ‘Open these up immediately!’ All they had in terms of an opening was a hole, a tiny hole barely enough to fit a cigarette. We had them opened up. There were people coming out of each door we unlocked. In there you can’t sit down or stand sideways, you have to stand upright at all times. Some had been there for weeks, others for months. They gave us phone numbers, saying ‘Let my family know I’m here’. Looking for a pen of sorts, we found our eyeliners and used them to write those numbers on our hands. We got them to have some fresh air and a drink of water. What they had done, whether they were terrorists or not, or Dev-Sol (the Revolutionary Left) or anarchists I can’t say because I don’t know. At that moment, for us, they were simply human. For we had experienced the same suffering…

Quoted from testimonies in the book 80’lerde Lubunya Olmak (Being Queer in the 80s), a work of oral history with nine trans women conducted by the Siyah Pembe Üçgen (“Black Pink Triangle”) İzmir Association.

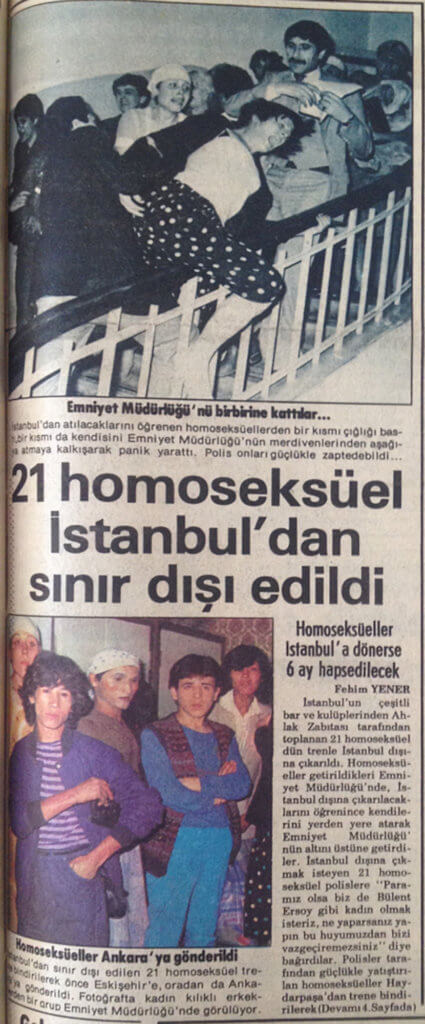

This did not change after the September 12 military coup either. The oppression, restrictions and torture brought about by the coup for most all factions of society were also the case for the LGBTI+s of the period. A circular issued in 1981 by the then Minister of the Interior Selahattin Çetiner of military background announced that “No one dressing in drag shall be employed in bars, clubs, cafés and music halls”. As a result of this performance ban lasting almost a decade, gay and trans people working as singers and dancer boys (köçek) were condemned to unemployment. The only option they were left with was earning a living through sex work. Finding housing and employment kept becoming more and more of a challenge for this prohibited group of people. Sex change operations were cancelled and banned.

In the 1980s everything was more heightened than usual, more brutal and cruel: They would hunt us transvestites, transsexuals and gays down wherever they found us – in our homes, workplaces, the market and on the street… They would take those they rounded up to the then infamous Sansaryan Inn in Sirkeci, to the Police Department that is. Oh what torture and perversion that Sansaryan Inn witnessed in its day… We were taken up to the top floor of the station. There was a massive door. As I walked through, I read an inscription saying ‘There is no God here, and the Prophet is out on vacation’. Now the Police say ‘No, there was no such thing’. In this country you should always suspect something is not quite right when you hear someone say ‘No, that didn’t happen’. When some day one finally stands up and says ‘Yes, it did’ everything will get better.

Quoted from 80’lerde Lubunya Olmak (Being Queer in the 80s).

Torture intensified and became even more institutionalized during and after the military coup of September 12. The Istanbul Police Department at Sanasaryan Inn in Sirkeci and the Hospital of Venereal Diseases known as “Cancan” operated in tandem. Trans people arrested by police teams were kept confined in these places at times for days on end. During these prolonged detention periods police officers such as the torturer nicknamed “Kırbaç” (i.e. “The Whip”) would force trans women into sexual intercourse, cut their hair and beat them with clubs. Women were asked where they were from and ‘bastinadoed’ – that is, had their feet whipped or caned – as many times as the car plate number of their hometown. Life had become nothing but a wild chase full of soldiers and police officers – even ordinary watchmen took on a major role in the whole ordeal.

In 1988, as a result of legal amendments made for Bülent Ersoy upon Turgut Özal’s initiative transgender reassignment surgery was legalized and the performance ban lifted. Yet increasing murders, torture and violence also brought about attempts at collective organizing. İbrahim Eren and company worked to establish a Radical Greens Party and LGBTI+ individuals also took part in this process. The very first LGBTI+ organization was started in 1986, and in April 1987 a sit-in and hunger strikes were staged in Taksim Square demanding an end to violence and to being driven out of their territory, as well as freedom to undergo surgery and carry pink identity cards.

MINORITY AND RELIGOUS COMMMUNITY FOUNDATIONS

Based on a Declaration (“Beyanname”) issued in 1936, over 30 immovable assets acquired through donation or purchase from 1936 to 1970 within the legal framework of its day were seized without compensation from non-Muslim community foundations in light of Court of Appeals decisions and transferred to their original owners or the State Treasury. Various sources cite the number of confiscated Greek, Armenian and Assyrian properties belonging to religious community foundations as 206.

Here are Hrant Dink’s words on the 1936 Declaration: “A new Law on Foundations numbered 2762 was promulgated in 1936. As per this law, minority foundations were obligated to list their sources of income and real estate and declare these to the General Directorate of Foundations in lists that were called the ‘36 Declarations’. These declarations were simply lists. They contained no reminder, understanding or statement that the declaration in question would serve from then on as a ‘foundation charter’ or ‘deed of trust’. Another detail these declarations didn’t or weren’t asked to include was whether the foundation could acquire new property after this date. There was no question of this sort, and as such foundations were not asked to respond in the affirmative or negative.

At present, however, these declarations are accepted as charters according to Court of Appeals decisions, and foundations are not permitted to add new sources of income to their existing properties. In practice the repercussions are not even limited to preventing the acquisition of new property, but those obtained after 1936 are being seized from minority foundations through lawsuits filed by the Directorate General of Foundations and handed back to their former owners. Our institutions are therefore currently unable to purchase or accept as donations any kind of property.

How have we reached this point? In 1971, the first of what we call ‘the 36 Declaration Cases’ began between the Balıklı Greek Hospital Foundation Board of Trustees and the State Treasury, and was later taken to the Court of Appeals General Assembly of Civil Chambers, which unanimously ruled on the 8th of May 1974 that the foundation could not legally acquire any new property other than those listed in its ‘36 Declaration. This Court of Appeals decision established ‘legal precedent’ for similar lawsuits brought by the Treasury or Directorate General of Foundations against minority foundations, and played a decisive role in future unfavourable verdicts they received.

Unfortunately, the Court of Appeals General Assembly of Civil Chambers fell into a grave error in reaching this decision, considering minority communities in Turkey as ‘non-Turkish peoples’ and stating that corporate bodies composed of non-Turkish persons were prohibited from acquiring real estate. This injustice must be undone.

Up until present over 30 different buildings and plots of land belonging to foundations of the Armenian community have been confiscated in this manner, and returned to former owners.

The state bureaucracy denied any responsibility for this injustice, putting it on the judiciary instead by saying, ‘What can we do, the judiciary is independent in Turkey’. This is, however not rightful defense, but typical evasion. Those wielding political power could, if they so desired, easily solve this issue through new legislation. And this they should, because the current state is a disgrace to democracy.”

The matter of “Minority Foundations” became a major point of contention in the harmonization process with the European Union as well. This practice preventing non-Muslim minority foundations from acquiring new real estate through purchase or donation and seizing immovables they had acquired since 1936 was found in violation of citizenship, minority and human rights. Following European Court of Human Rights decisions important amendents were made to the law in 2002, 2003 and 2008.

Today, confiscated foundation properties worth millions are being returned though at a snail’s pace. According to various studies there are currently 161 active minority community foundations, 74 of which belong to Greeks, 5 to Armenians, 18 to Jews, 9 to Assyrians, 3 to Chaldeans, 2 to Bulgarians, 1 to Georgians, 1 to the Orthodox and 1 to the Independent Turkish Orthodox.